This Edition of Ecstatic features Josh Tiessen. This month’s features are brought to you in partnership with Fuller Seminary.

Josh Tiessen is an international award-winning artist based in Canada, best known for his hyper-surreal and uniquely shaped oil paintings. His pieces often delve into the interaction between the natural world and humanity, drawing on his studies in philosophy and theology. His latest show, Vanitas and Viriditas, is an exploration of two divergent perspectives on wisdom and how we might flourish in a modern society filled with facts but mired in confusion.

Ekstasis Editor, Conor Sweetman, sat down for a conversation with Josh to expand on his ideas and talk art. Answers are edited for length and clarity.

CS: To start off, I'm curious: how do we find life in the midst of an apocalyptic environment? This question is pretty in the weeds right off the bat because I'm thinking along similar lines in terms of the next print issue for Ekstasis and this whole idea of the garden of the future.

In your explanation for your new show in New York City,Vanitas and Viriditas, I noticed the term “holy greening” which Hildegard of Bingen came up with. Tell me a little bit about this concept, and whether it only arises in the environment embodied by the character of Sophia? Can you also find this greening even in an ecclesiastical, apocalyptic landscape as well?

JT: Yes, that's a fantastic question. I think Sophia—the female personification of wisdom in Proverbs—expands upon what it looks like to be a wise person and to live a good life; and I've drawn on Proverbs as a whole to really figure out how we even develop virtues in regards to the natural world. Her vision is definitely more about wonder, and humility, and simplicity, and awe, and how we live in a moral universe when we heed her wisest advice. And so when we live in such a way that follows God's commands as the creator of the cosmos, we flourish, and there's benefits and rewards where justice and goodness prevail. But then it's true that Ecclesiastes, with its embodiment in the character of Qohelet is, in a sense, also a teacher—his perspective and wisdom is divergent, but I think it can be complementary because, in a way, it's dispelling a lot of the modern idols in our society—things like toil, and pleasure, and consumption, and greed.

And so he’s saying that not everything in life makes sense, and life is enigmatic and strange and goodness isn't always rewarded… wise people and good people both suffer, and beauty is fleeting. But I think there is a wisdom there because both Sophia and Qohelet return to the fear of the Lord as the beginning of wisdom. There is a respect; a reverential awe. Sometimes people get hung up on that word “fear” of the Lord. But understood properly, it's really about remembering our creator. And so I think if you take both of those perspectives of wisdom, you can have more of a holistic world view that I think both are necessary.

CS: Yeah. I feel like the comparative landscapes of Sophia and Qohelet are contrasted in their visualization, and it can be easy to make the value judgment that Sophia's landscape is good, and Qohelet’s landscape is bad. But then in the actual characters themselves, I don't see that same contrast necessarily. It doesn't look like Qohelet is villainous or sinister; he hasn’t embodied the apocalypse, even though he's surrounded by it. So, these two forms of wisdom… You said they were complementary—is that your main thinking in this series?

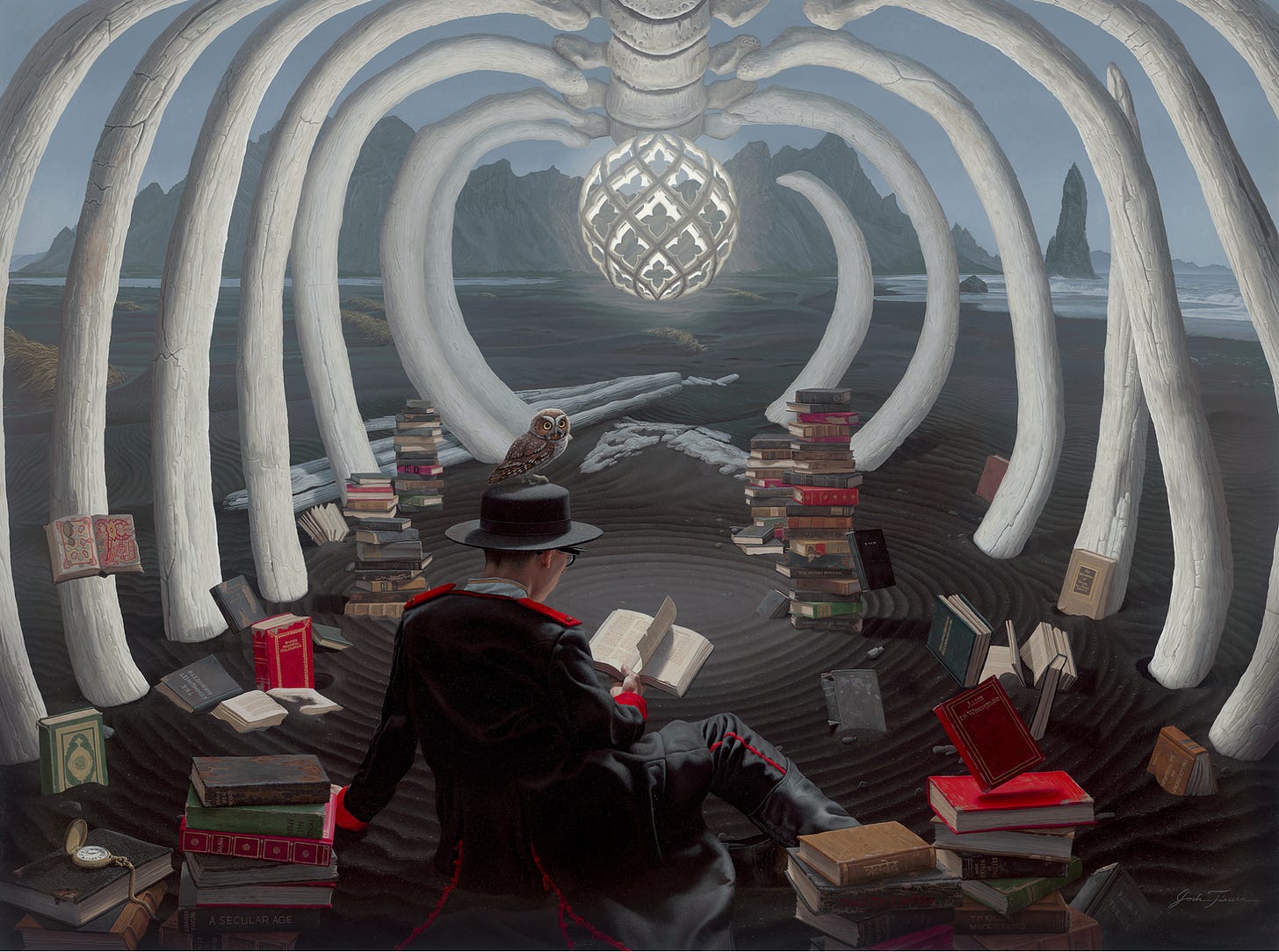

JT: I think you really captured what I'm trying to go for in this series—where there is a nuance, and it's true that the paintings Qohelet occupies are full of black sand and barren landscapes. There's bones like with the whale rib cage in Swallowed by Knowledge or the skull that he's holding in Memento Mori but yet he’s on a quest for meaning. I think his paintings are dark and a bit more macabre because he goes places that a lot of people don't want to go in our world where things like technology and pleasure kind of blind us. So in a sense, he's like the Solomon figure who is trying to find meeting in all of these things but eventually finds them empty and futile; he can seem disenchanted… But I think there is a wisdom in that, that we can heed our world in a way that’s existentialist, but doesn’t necessarily end up in nihilism.

In the final painting, Alpha and Omega, he's coming to see Sophia, she's carrying this tree of life which represents wisdom. Her world is breaking into his world. And so I think there is some sense in which ultimately, he is guided by Lady Wisdom, but he provides the balance to where Sophia could be taken. When you just look at the Book of Proverbs, there can be this kind of naive optimism for the world or this kind of karmic transactional relationship that I do good and I get rewarded, whereas in real life, it's a lot more messy than that. So I think they provide balance to one another.

CS: Yeah, that's really good. And it kind of leads me into my next question about Sophia—and you almost answered it in that last part of the part there, but, when I look at some of the pastoral idealism of the Sophia landscapes, it reminds me of a kind of romantic, poetic view of the world. In this way, like for William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, there is an expression of naivety where it seems like nature is absolute good; that there is truth and goodness implicit in nature and we only need to avail ourselves to it in order to be refined as a human being. So do you think that they went too far on that track? Would you say there's any counterbalance to ecological naivety, so to speak?

JT: It's interesting you bring up romantic poetry, because my three butterfly and moth paintings, Augeries of Innocence Part I, II, III, actually comes from William Blake's poetry. And I have the quote up here:

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

…Kill not the Moth nor Butterfly

For the Last Judgment draweth nigh”

It's beautiful, right? It shows an enchantment with the world and an emphasis on innocence. And so I see that both in Proverbs when it talks about how the ant and the lizard are wise creatures that we can learn from, and also in the book of Job, when it talks about how we should “Ask the animals and they will teach you… The breath of the Lord is in every creature.” I think that enchantment is necessary because in a secular age, we look at the world from a mechanistic or more utilitarian way of what it can do to benefit us. But I see where animals—and this is aligned with a lot of indigenous world views—are seen as an elder brother or sister. They've been here longer, and we can learn from them. And I think that's even the perspective throughout the wisdom books in the Bible,

However there is this reality that Soren Kirkegaard points out, where the wanderer becomes disenchanted because he can't even connect with the natural world; the human concerns that we have about life after death and what's the meaning of all of this—it’s not something that animals can ponder or contemplate. I'm surrounded by environmentalist types and there's even that disconnect that I fear in our day. I don't think that nature, in and of itself, can teach us wisdom. I think it can point to certain things, but ultimately it again returns back to the Creator behind the creation through which we can see the goodness of the natural world. But in itself, we’ll encounter the vanity of trying to find our full meaning and purpose within nature.

CS: That's really interesting to think about. On the technological side, do you see any possibility of enchantment or re-enchantment within the wasteland and the actual use of technology, even something as simplistic as massive amounts of reading, as is depicted in Swallowed by Knowledge?

JT: I certainly don't have any issue with learning and knowledge. I love to be well-read as far as possible, and I wanted to include books from all different disciplines, from politics to philosophy to religion, great novels and literature. But I think when it becomes overblown or ultimate in our lives, when we don't recognize our human limits and fallibility, that's when the pursuit of knowledge can be problematic. And that's the same with technology, where we begin to grasp toward a transhumanist future where we have this incredible omniscience and we can be all-knowing—and this is where it ties back into the theme of the series—we become mired in information in our society and have little wisdom, as the quote goes from T.S. Eliot.

CS: Did you have a personal, revelatory moment that led you to want to work through the symbolism of the series?

JT: Well, I think in my previous painting series Streams in the Wasteland, which spanned two exhibitions and a monograph book, I was able to delve deeper into the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible and to address some of these macro vantage points of nature and human civilizations that were wayward. And in this new series, I wanted to transition more to the micro perspective of what it looks like as individuals to become a wise person in our modern age.

Books like Steven Bouma-Prediger’s book Earthkeeping and Character was helpful because we can talk a lot about all of the concepts and philosophies for grappling and tackling the world's problems, environmental philosophies, et cetera. But oftentimes we talk too much about “what should we do?” as opposed to “who should we be as people?” And that's where Aristotle's concept of virtue theory has really come into play in modern life. Because what does it mean to be a hopeful person, a person who's just and courageous as opposed to one in the grip of vices like greed and self-centeredness which are driving a lot of the problems in our society?

And so to your question, it's been a gradual progression of discovery, like with any painting series. I don't just start out from the very beginning and think, “Okay, I'm going to create 17 paintings… They're all going to be about this.” But this has been a journey of discovery, and while I'm painting and processing, I find these ideas just naturally develop.

CS: Through this series and your own personal journey, what would you like to leave as a parting word for the most important thing that you see for our current environment and context?

JT: Wow. That's a big question. Well, there are many ways I could take that, but I hope that the painting series, along with the stories that go with them, would open up dialogue and discussion of what it looks like to even think about wisdom. Oftentimes we think of wisdom as being something that's very cerebral and it's in our heads and something that we discuss. But as you probably know, the study of philosophy, the word itself, means “a love of wisdom.” And a Hebrew biblical understanding of wisdom is “skill in living” and living well. And so it's actually a lot more embodied. We see how in the Old Testament, in building the tabernacle and temple, those artisans were told to be filled with wisdom, to create artistic designs. And Solomon was knowledgeable in botany and all these scientific fields as well as poetry.

So, I think what I'd like to leave people with is that wisdom is a whole way of life. And it's something that we cultivate, and it's not always black and white like we think of with morality per se, but nor is it something that is just inner wisdom that we figure out for ourselves—there is a cosmic order that we live in within the universe, and wisdom is this blueprint that we can align our lives to—but the things like community and embodied living is how we work out and express wisdom in our communities and societies.

Josh Tiessen

Artist & Writer

Josh Tiessen is a professional fine artist, speaker, and writer based in Stoney Creek, ON. He has had solo exhibitions in galleries from New York to LA. www.joshtiessen.com

Thoughts on Josh’s interview? Leave a like and share in the comments!

Wow. What an amazing conversation about uncovering the mysteries of life, art, literature and faith. The pursuit of timeless ethos in a post-modernist world. Brilliant!

I just finished James K A Smith’s Imagining The Kingdom and this entire exchange feels like it was lifted from those pages! Great stuff!