Building Somebody Else's Cathedral

The undeniable and uncomfortable call to write a first novel

This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic features Mike Bonikowsky

For the past dozen or more years, I’ve been writing a novel. I wrote a first draft, and that was easy. I wrote it for myself, an escapist fantasy of wish-fulfillment, an idealized version of myself doing an idealized version of my job. It was enjoyable. There was a lot of fun world-building to do, playing in that big old sandbox, writing fictional versions of my friends and enemies. It made me happy, and I could tell people I was writing a novel but not actually have to produce anything that might leave me open to criticism. It was a hobby, like birdwatching, or painting Warhammer miniatures.

I finished the first draft, sent it to some safely uncritical friends, closed my laptop, and went to go play video games. But I found that I couldn’t. The novel wasn’t letting me. The story I had playfully told myself began telling itself to me. Characters I thought I had invented took on dimensions I didn’t know they had, and began saying things I didn’t want to hear. The novel began to imbue my daily waking life with a certain heaviness, like radiation building up in the marrow of my bones.

And the uncritical friends turned out to not be as benignly affirming as I had hoped. “It’s good,” they said, and this was all I wanted to hear from them. But they didn’t stop there. “But it’s not done. You didn’t think it was done, did you? You need to rewrite it, and fix this and this and this.” This was not at all what I wanted to hear from them. This was not the role they were meant to be filling in my little affirmation liturgy. But they were better friends than that, and so I was bullied into a second draft.

The Shepherd of Princes refused to stay in the compartment of my life I had written it to fill. It had seeped into everything now. It was with me at work. It was with me when I tried to play video games after work, suggesting it might be a better use of my free time. It lay down with me to sleep at the end of the day, whispering the story of itself into my ear and insisting I get out of bed and write it down. It informed my anxious dreams, and remained with me when I woke up on Saturday morning. It refused to let me rest until I wrote it down, and then wrote it down better.

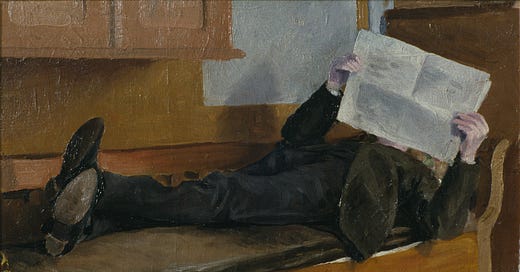

So I went back to the laptop, when I would rather be doing almost anything else, and I pecked away on a second draft. This time it wasn’t fun. I wasn’t doing it because I wanted to, but because for some reason I now had to. It felt like work. It felt like a job. It felt like what by the grace of God it had become: a vocation.

Somewhere in the process of its creation, the novel had ceased to be mine. It had left me behind, and become its own entity. It belonged to itself now, or to the friends I now wished I had not asked to read it, or to Someone above and behind all of us, but certainly not to me. I was no longer serving myself by engaging in a fun pretentious hobby. I was now serving the work I had been given to do. This was unexpected, and oddly freeing. I do things I don’t want to do all the time, not because they are fun or because I get paid for them but because they are necessary and worth doing in and of themselves. I plow the driveway when it snows. I plunge the toilet when it’s plugged. I feed my kids when they’re hungry. It’s called being a human being. To the list of human duties I simply added write the novel until it’s finished.

I am fortunate enough to have another vocation, for which I am paid. I work as a caregiver with adults with developmental disabilities. It is not always easy work to do, and it is not always fun, but it is always worth the time and effort. It is always worth the exhaustion at the end of the day. It is often menial, but it is never pointless.

The Shepherd of Princes is about this work, and has much in common with it. As it changed from a personal vanity project to this new, better, thing, it also became increasingly a part of my larger, deeper vocation as a caregiver. I would do the work, and come home and write about the work. They were two sides of the same coin, two different shifts at the same job.

You have never “finished” a vocational work. You just show up and do the work that day puts in front of you until sleep takes you, and then you wake up and do the next. To think of an ending, be it retirement or publishing, is fatal. How and when the work ends is none of your business. Don’t you have enough to think about? It is God, the voice behind the vocation, who decides when you finish. But you decide how well.

This is how it has been with The Shepherd of Princes. It stopped being about me a long time ago, which is the only way it has actually come into being. I had to die to the identity of the author, die to my own presence in the work and my sense of ownership over it. Only when the novel stopped being mine did I become free to write it. I had to let other people read it and speak the truth to me about it. I had to listen to my friends who insisted that I was not done, that I had to rewrite this section, then rewrite it again. I had to kill my darlings on the order of my friends. I am, at bottom, a very lazy person. I would never work this hard on a personal hobby. But to keep from disappointing friends that I loved, I would.

C.S. Lewis says that God’s intention is to bring a person “...To a state of mind in which he could design the best cathedral in the world, and know it to be the best, and rejoice in the fact, without being any more (or less) or otherwise glad at having done it than he would be if it had been done by another.”

I never understood how this was possible until I wrote my novel for the fifth time. By that time it was no longer mine in any real sense. It belonged to itself, that is to say, to God, and to the legion of friends and fellow artists who by that time had begun to help me shape the work into what it was meant to be. We were working together now, like neighbors raising a barn.

And now the reader joins in the work. By the grace of God and the friends I’ve made at Solum Literary Press, Shepherd is a real book now, proofread, copyedited, illustrated, and printed. It is truly beyond my reach now, and has continued to become itself in partnership with its true owners, those who read it. This is the real gift: People talk to me about the story, and I don’t recognize it. They have taken things from it as foundational that I didn’t even realize were there. It’s as if they have read a different story than the one I wrote, and it’s a better one, one I wish that I could read.

And maybe they have. Maybe they’ve read the real story, the one I was writing without knowing what I was doing, one word at a time, no more or less creating than the bricklayer who creates the cathedral brick by brick, following a blueprint he did not draft and cannot see.

Mike Bonikowsky

Author & Caregiver

Mike lives in Melancthon, Ontario, with his wife and kids and chickens and rabbits. He works as a caregiver for men and women with developmental disabilities. His first novel The Shepherd of Princes has just come out with Solum Literary Press. What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

I don't usually read short pieces like this. I had no intention of reading this one. I don't even know how I came to have it. However, after reading the first two sentences, I could not stop reading it. It tells a story with such flow that it would require more effort to stop than to continue.

Hello there, I have not written a novel, but I do understand the part about a piece of writing that takes on a life of its own. Glad you finished it. I enjoyed your essay so I can put your book on my list of things to read. Thanks for sharing.