This Weekly Edition of Inkwell features Scott Cairns

DURING THE FALL of my junior year in college, having registered the previous spring for what would be my second college poetry workshop, I arrived at the appointed classroom to discover a hall overflowing with students. Over the summer, unbeknownst to me, our workshop had been assigned to Annie Dillard, who had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize the previous spring for her Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

Nearly a hundred students crowded the hall, wanting to enter a classroom that could have held maybe twenty-five, at most. I vividly remember the moment Annie showed up and witnessed the mayhem. I can still hear her voice rising over the ruckus, saying “No, no. This isn’t going to work. Heads up!” She called out, “I’m adding no one to the roll sheet—no one who isn’t already in the class will be getting into the class. Sorry! I’m really sorry.”

The general disappointment was audible as groaning filled the hall. “I’ll read through the roll sheet,” she said, “and if your name is on the list, make your way into the classroom to take a seat. If your name is not on the list, you’ll need to split.”

My name was on the list.

I made my way into the room. Feeling way out of my depth, I sat near the back. When all was said and done, fifteen of us partook in a weekly, three-hour workshop-seminar-philosophical meditation for a fall term that would change our lives.

LIKE MOST OF MY PEERS, I had suffered up to that point a commonplace misunderstanding of contemporary poetry. Most of us had been led to believe—by teachers, professors, and the general 1970s vibe—that poetry was but a curious and encoded species of self-expression. Annie Dillard wasn’t mean about wising me up, but neither was she shy about it. After a couple weeks of class, she suggested that I stop by her office during her office hours.

Once in her office, lined with overflowing bookshelves, she asked me to read aloud a few of the poems I’d been working on.

“Ah,” she said, “you’re a stylist! You know how to make sentences!”

I was beaming, even if I didn’t quite fathom at the time what she meant by “stylist.”

“Your poems are lovely little anecdotes, with some very lovely images.”

I was no longer beaming. I was pleased that my images were lovely, but less happy to think of my poems as “lovely little anecdotes.” I asked her what I should do next and how I could make my poems better.

“Do you know Coleridge much?” she asked. “Do you know his ‘Kubla Khan’”?

I did not.

“Well,” she said, “listen to this.” She pulled a volume from the shelf behind her and opened to “Kubla Kahn.” She read the poem aloud. She read it a second time, and then a third.

She put the book back in its place, saying, “I want you to read ’Kubla Khan,’ and pore over every word of it. I want you to say the poem aloud every day until our next class. And I want you to do that, first thing, whenever you sit down to work on a poem.”

Got it.

Did it.

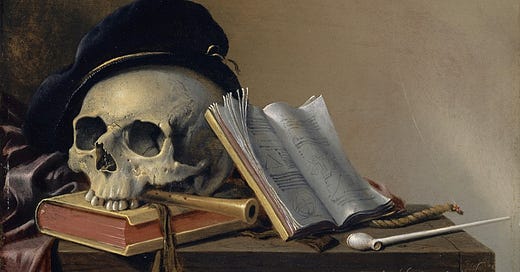

This quiet exercise began my journey to actual poetry. More than that, the exercise became something of a discipline. So began my longstanding conversation with the dead.

MINE WAS, even so, an admittedly slow journey. Many of my poems composed during my college days, as well as most throughout my MA at Hollins College, and my MFA at Bowling Green State University, remained anecdotal, documentary, for the most part, little but expressions of an experience or an idea that preceded the poem on the page. That is to say, my poems remained largely retrospective, results of examining my past, and mining those personal experiences for something worth sharing with an ostensible reader.

But the dead wouldn’t have it.

The dead poets over whose works I pored eventually, by example, taught me that actual poems were not to be understood as documents of meaning made, but as scenes of ongoing meaning-making. The best poems, in my estimation, proved to be those that provoked imagistic, ideational, and linguistic reply, and the very best poems proved to be those that would continue to offer such provocation every time I pored over their words on the page.

DURING MY DOCTORAL STUDIES at the University of Utah, where I was blessed to study with Mark Strand, Larry Levis, and the incomparable Richard Howard, I began reading widely in poetry, philosophy, patristic theology, and spiritual writings of many sorts. I also started reading and considering midrashim and other rabbinic texts composed in response to difficult or ambiguous scriptural texts. That is—thanks to the rabbinic darshans—I learned to open the texts before me.

I was assigned a study carrell in the university library that was, thank God, adjacent to the stacks holding English poetry. My habit was to pull a volume or two from the stacks, and retire to my carrell for the morning. There, I would steep in a series of lines, copy those lines onto a yellow legal pad, and open, expand, and annotate the terms before me.

In the comfort of my study carrell, I also took to reading patristic theology, hermeneutics and the philosophy of language. I fell in love with Athanasios, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and Basil the Great. I fell in love with the dense and provocative prose of George Steiner.

One revelation along the way—one that still underwrites what was to me a new disposition towards what words are and what words do—arrived during my reading of Truth and Method by Hans Georg Gadamer. In that astonishing work, Gadamer assisted my apprehension that words are more than signs pointing to things. He wrote: “In Greek, the expression for ‘word,’ onoma, also means ‘name,’ and especially ‘proper name’—i.e., the name by which something is called.” He claimed that, historically, for most readers throughout history, a word was simply that, a name referring to a thing. Gadamer also drew my attention to an exhilarating alternative, that the expression for “word” in Hebrew, davar, recognizes words as being more than names for things, that they are also things, things bearing agency—which includes the power to make. This is, of course, an implicit understanding that dates back to the redaction of Genesis, in which the Lord is said to have spoken all creation into being by his having uttered the words, Let there be.

At some point during my reading and re-reading of Gadamer’s book, I came to a new sense of what a genuine poem must be: a made thing capable of further making.

In Gadamer’s contrasting Hellenic and Hebraic senses of words, I glimpsed a profound temporal difference. Whereas words serving merely as names for things necessarily pointed to past phenomena—the ideas or feelings that might have preceded a writer’s setting pen to paper—words understood as things bearing creative agency could also gesture toward a future, could also construct a future. The first activity was purely retrospective; the second was also prospective. My putting words on paper became my way to press language for information; I was no longer writing what I already had thought to say, but I began writing to discover what it was I might yet say, trusting my words to lead me into new apprehension.

I also began corresponding with the dead.

ANNIE DILLARD’S off-the-cuff suggestion offered to me in my early twenties—that I precede my writing time with reading time—became the foundation of a lifelong practice. Her advice to begin with Coleridge awakened me to the efficacy of engaging with poets who preceded me. In short order, I gathered a trustworthy coterie of poets who spoke to me. Soon after, I began to speak back to them.

On my writing desk to this day, I keep the various collected works of the following: Coleridge, Dickinson, Cavafy, Rilke, Eliot, Stevens, Frost, Auden, Seferis, Akhmatova, and Bishop. Others periodically join the rotation for months at a time, but these names remain ever at hand. When it is time to write, I begin by reading. I lift a volume from the stack, open it to a familiar passage, and—with yet another yellow legal pad lying by the book—copy lines, expand lines, and respond to those lines with lines of my own. My new poems become my replies to their generous poems.

We continue to carry on a very lively correspondence.

Above and elsewhere, I have referred to them as the dead, but they are as alive to me as anyone walking my neighborhood. They are living mentors from whom I continue to learn. Moreover, far as I can tell, they are my primary audience.

WHILE IT IS by no means the first evidence of my longstanding practice, my most recent poetry collection, Correspondence with My Greeks, is perhaps my most overt testimony of how I roll. That collection came about from my reading through an entire century of modern and contemporary Greek poetry, and my discovery that each of the nearly seventy poets I included in the collection had made poems that insisted on my engaging them, even to the point of my making replies to their exhilarating works.

Every time I lift a book to read—be it poetry, fiction, philosophy, patristic theology, or even sacred scripture—I re-enter the conversation, the centuries-old conversation that shapes us even as we, by our responses, shape it.

T. S. Eliot’s essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent” comes again to mind. He has written that “[n]o poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead.”

This reciprocal model that Eliot affirms might be readily likened to a correspondence, a conversation, a dialogic relationship that began centuries ago, continuing to the present day, and promising to continue endlessly into the future.

I have, by last count, been teaching some version of this vision since my first teaching assistantship in 1979. You do the math.

My hope has been that, just as Annie Dillard introduced me to this conversation in 1975, I can convince my students to join in. As Eliot insists in his essay, it is not enough merely to repeat the received matter; one must extend it.

IN CLOSING, I offer this very new poem, “Chemo with Coleridge,” from my forthcoming collection, Makarios, slated to appear in 2026. I trust that the poem’s correspondence to Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” is evident, and that my offering the poem will illustrate that Mr. Coleridge and I continue our longstanding correspondence. May it be blessed.

Chemo with Coleridge

The port implanted in my chest will serve

to deliver directly to my heart

the pharmakon my doctor has allegedmight just give my malicious blood a nudge

in the general direction of its

atonement, my repair. May it be blessed.To keep my mind otherwise engaged, I

have brought my longtime correspondent,

Mr. Coleridge, his collected works.His collected works are working their charms

to the degree that hours pass without my

dwelling on the manifestly dire straitsof those who sit adjacent, receiving

their own, special mix of remedial

poisons. Thank you, dear Mr. Coleridge;so long as I do not dwell overmuch

on their gaunt and sallow visages, my own

languishing is less likely to drag meto grim self-pity, which seems far too much

like death. My poring over these beloved,

demanding poems infuses my anxiousheart with a balm concocted in concert

and correspondence with the terms I hold

in hand. As I read, I say the words, eachsyllable, within my mind, my very nous.

I say the words there, listening, that I

might revive their symphony within me,that from this ice I might yet build a dome.

Scott Cairns

Poet & Professor

Scott is consultant to the new MFA in Creative Writing program at Whitworth University. Author of Lacunae: New Poems (Paraclete Press, November 2023) & Correspondence with My Greeks (Slant Books, 2024). He also contributed the opening interview of the

’s recently released An Axe for the Frozen Sea, which an Inkwell editor enjoyed over a pint in Oxford.What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

A wonderful essay for all poets and writers and any one of a poetic heart, whether they have taken pen in hand or not. Insightful and instructive. It opens avenues of creation we desperately need. Now it is time to go write a poem with new tools and fresh light.

An ongoing conversation! Yes, this is what reading and writing affords. Cairns provides a helpful lens for both reader and writer to assess their desire to speak into the ever growing body of literature that shapes ourselves and the world. I have never felt that the anxiety of influence accurately captures this fascination (at least not wholly). Cairns demonstrates that writing is an opportunity to make meaning, and when we respond deliberately to those who have gone before, we can travel further. I love a poem as "a made thing capable of further making." We ourselves are being made in the act of wrestling words to the page. Thank you for this!