This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic features E. Lily Yu

E. Lily Yu is an award-winning novelist and short-story writer, with The New York Times Book Review lauding her novel, On Fragile Waves, as ”tremendous… devastating and perfect.” Accolades have included the Washington State Book Award and the Artist Trust LaSalle Storyteller Award in 2017.

It’s not unusual for creative people to encounter unexpected turns in their work. That could be said of E. Lily Yu’s newest endeavor, Break, Blow, Burn, and Make: A Writer’s Thoughts on Creation. “The book itself was a surprise,” she recounts in this interview. Years of reading, writing, reflecting, and observing the wider culture prompted her to conclude that, as she says, “no one else was presently seeing or saying the things I thought needed to be said.”

I was struck by her wide reading, her wise explorations of Scripture, as well as observations on a range of writers such as G. K. Chesterton, Madeleine L’Engle, and James Baldwin. Throughout the book’s pages appear cultural commentary, exploration of the writing craft, and vivid, even visceral poetic imagery. A moving chapter, “Courage,” will encourage those wanting hope for their own creative efforts and surprising turns.

Timothy Jones: Early in your book you paraphrase the poet Czesław Miłosz, who describes a reader pinned down by machine-gun fire in an embattled street watching cobblestones flip onto their sides. Readers who have lived through such experiences of what he calls “naked reality” lose interest in what is not firmly rooted in the real. You obviously are interested in writing (and reading) that has depth and truth and urgency, and that passion comes out in the book. What led you to that insistence on those qualities?

E. Lily Yu: What I have written about is a quiet loss, not just of what Czesław Miłosz calls “naked reality,” but of the qualities of wisdom, love, and depth, among others. I am not the first to do so, though I began to count these things when I felt their absence in the recently published books I was reading. It is difficult to talk about them without confusing others because the meanings of those words have shifted when used by those without real understanding of them. I don’t think it has ever been easy to talk about anything that is timeless or deep, but now, in a time when people are obsessed with appearance and public performance and immediacy, it feels nearly impossible. Alienation from physical reality exacerbates the problem. When people can spend much of their lives indoors, on glass screens, online, interacting with shadows on a wall, how can you understand me or know I have gotten the description exact when I describe the twisting drag of a fish on a line or the snappy sourness of red huckleberries, much less what life and death are?

TJ: I love books on the creative process, especially as it relates to writing. As you wrote, what guided you in picking up varied implements and tools from the writer’s kit?

ELY: Some of it came from frustration at what I was reading—both at what basic elements were missing from books, and at the shallow and incorrect ways in which certain things were taught, that had no relationship to my understanding of writing. Some of it came from prior responses I have given to questions that students or audiences asked me.

TJ: At the beginning, you write, “the decision to keep bees, to write, or to follow Christ is usually made with a vague and incomplete sense of what will be required: a hive, a few notebooks and pens, or a hymnal and a church.” When you began to write Break, Blow, Burn, and Make in earnest, did you find surprises along the way?

ELY: The book itself was a surprise, since I hadn’t ever considered nonfiction. I had been writing essays for my newsletter for several years when I saw that I had the beginnings of a book, that no one else was presently seeing or saying the things I thought needed to be said, and that if I didn’t write this book as a desperate dig of the paddle to turn the boat, I would wind up in a world where I could no longer write or find books that fed me.

TJ: Your title alludes to John Donne’s prayer, “Break, blow, burn, and make me new.” That suggests moments of breaking, but also the possibilities of something coming from within or from above that lifts the creative person to moments of joy. What do you say to an artist or writer or musician who’s discouraged?

ELY: I think Donne had the smithy in mind: anvil, forge, the cutting hardy upon which the heated rod is hammered until it breaks. Battering, heating, and breaking are all necessary to turn raw material into a useful and toughened form, but I imagine the experience of the metal is not a pleasant one. Only an understanding of the smith’s intent and the beautiful or worthy purpose toward which we are shaped can make the process a joyful one, and that understanding comes by grace.

I don’t think I can or should give advice to discouraged artists as a class, since the sources and causes of discouragement differ from person to person. Sometimes the discouragement is temporary and meant to be endured. Sometimes the door is firmly shut and the heart sickened, so that we give up. And in giving up what we were, we find our way to newness and growth.

TJ: You are pretty clear that writing—any creative endeavor—requires sacrifice. How have you found following your calling costly?

ELY: During research for the first novel, which has several scenes in Afghanistan, I found myself looking at insurance policies for death, dismemberment, medivac, and repatriation of remains, among other things, that priced out the loss of various body parts. There was a fairly thorough list of potential consequences that I had to be able to agree to, though none of them came to pass. More recently I wound up in a position where, because I had carefully examined a number of claims and found them to be unsupported by evidence, I could speak the truth and defend language, and so lose the vast majority of my friends and artistic communities, or remain silent and complicit with liars. I did pay a great deal in that case, though much less than what I was willing to pay. I do not like these situations. That said, there are compensations, including the people I have met as a result.

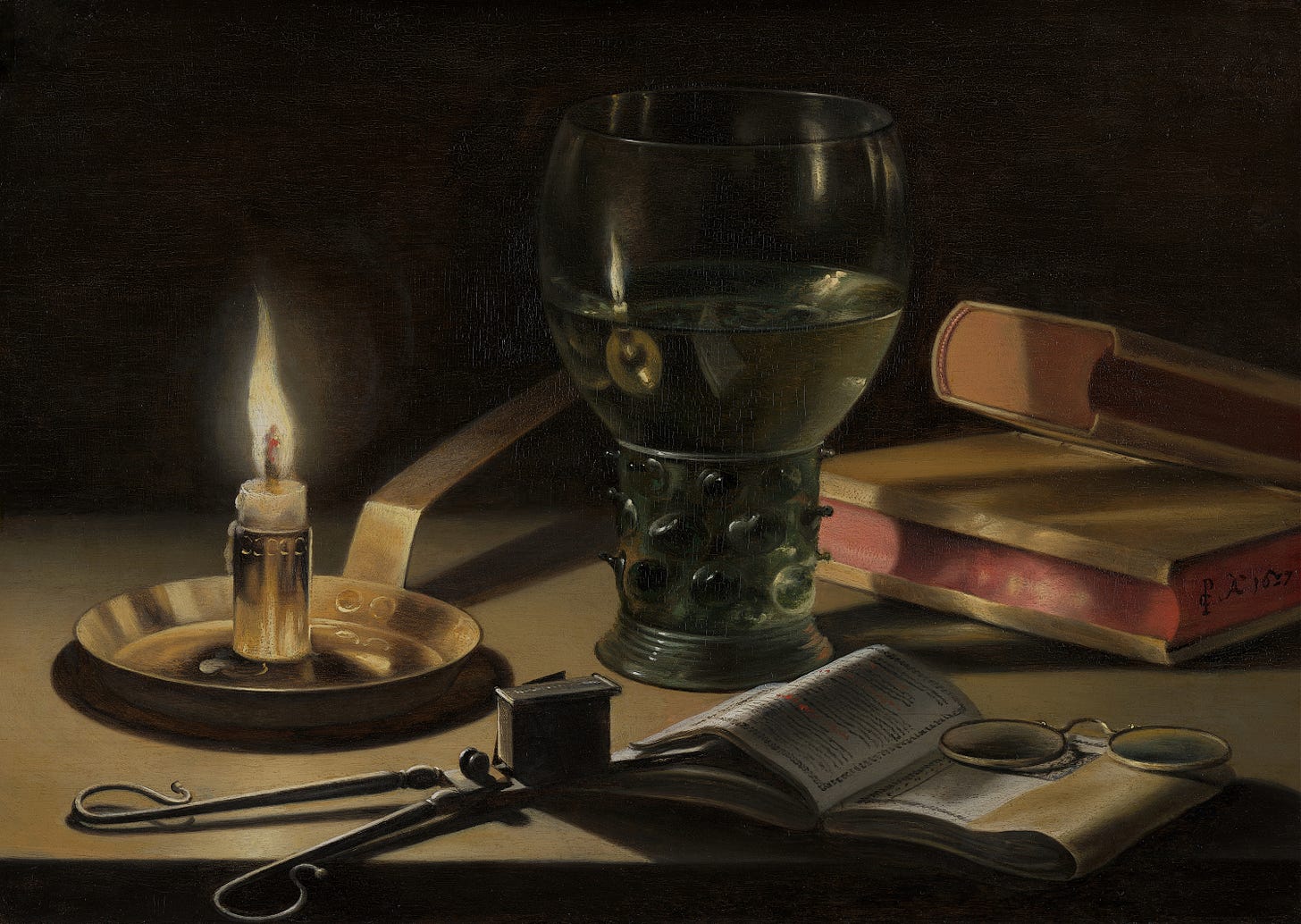

TJ: You say that creativity that is “incandescent” can lead us as readers (or viewers of art or listeners to music) to the risk of “being set alight ourselves. … We come close enough to catch fire.” Do you believe that much contemporary spiritual writing (or art) lacks that kind of fire?

ELY: “Incandescent” is the best descriptor I could come up with for the personal, subjective, transformative experience of certain works of art, which leave me permanently changed. That kind of work reaches into me—or rather something or Someone reaches through the work into me—and undoes and remakes me. It is the work that can be incandescent, not “creativity,” and the light in question passes out through the artist rather than originating in the artist’s self. I do not use “incandescent” as a synonym for “good.” I have read and enjoyed many fine, even excellent books that do not change me utterly, and I am glad that I have read them.

Readers tend to project their own experiences and expectations onto the passages where I talk about incandescent art, which I mention has always been rare, but seems to have disappeared altogether in the past decade. I have noticed a temptation to simplify what I am saying. I am not talking about modern versus classic books—examples are rare but present in both, and I also cite a video game—nor am I talking about Christian writing, which Christian readers tend to assume. Being an outsider, I had no real knowledge of Christian publishing before writing Break, Blow, Burn, and Make; I now know it is 2% of the book market. But I am talking about books in general. I have tried to delineate an experience that is difficult to describe, still more difficult to understand, but which I believe is vital to literature, for readers and writers alike, in the hope that like an endangered orchid it might be recognized, recovered, and propagated.

TJ: Sometimes the creative process, whether writing or sculpting or dancing or playing a musical instrument, involves drills and discipline. Other times, you note, in a kind of “flood” of insight and connections we are blessed “in the direct and palpable touch of the Creator’s hand.” You enlist the image of a wine barrel in which “a long fermentation occurs, and out of which the wine flows.” How do we make ourselves available for such moments brushed with the divine?

ELY: I am only describing what I am, not what others should be, in the hope that someone else recognizes what I am talking about and realizes that she is not alone. As for telling people how to come to God, I believe you are far more experienced and skillful than I am, and I would rather hear your answer than mine.

TJ: I’d say there is a similar dynamic at play in both. Jesus said, after all, “The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes.”

Another question: You have a good eye and evidence a rich concentration on what comes to us through the senses: bees hiving, “the fragrance blowing from winter daphne … a snow of cherry petals, or … the fairy fall of cottonwood.” Attention, you say, following Mary Oliver, is “the beginning of a rich and real life.” It’s harder than ever, isn’t it, in our distracted day, to cultivate such open-eyed awareness? How do you manage it?

ELY: The only time I am really alive, really living, is when I am paying attention, whether to a person, a subject I am studying, God, or an object in the world. Drawing from life, which requires you to look deeply at one thing for a long time, can help, as can meditation. But ultimately you have to develop a desire to live, which paradoxically is not common when our lives are safe and convenient. The taste and smell of food are never sharper than when you have been hungry for a long time, and you would see the world and the people around you very differently if you knew you would die tomorrow.

TJ: I love the chapter title “God the Collaborator,” and the prayer with which you open it: “God, what and when and how do you want me to write? God, help me.” How do you sense God guiding you toward what is next?

ELY: I think it is like being dragged on water skis behind a speeding motorboat when you don’t know how to water-ski. There is a lot of yelling. I try not to drown.

Timothy Jones

Author & Pastor

Timothy Jones is a widely published author of books helping huge Christian beliefs seem more accessible and inviting. He is currently writing about the expansive, extravagant love of God found in the Trinity. He blogs at revtimothyjones.com. What did you think of this interview? Share your thoughts with a comment!

This intriguing book is going to the top of my ever-expanding reading list! E. Lily Yu’s thoughtful & nuanced aesthetic perspective captures my interest. As this vision finds definition through its covering in “incandescent” grace, it encourages artists to connect to audiences authentically through shared brokenness and redemptive longing.

I’m stirred by the vision expressed in this interview, and can’t wait to get my hands on the book!