This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic is by Yi Ning Chiu

If there is an unofficial religion of the West, its liturgies can be found all over downtown San Francisco. The sky here swarms with billboards inscribed with different versions of the national statement of faith— promises that artificial intelligence software will optimize your productivity, that new wealth management programs will multiply what you own, that wellness apps will finally put your anxieties to rest—which, written out plainly, would say something about how money paired with human ingenuity can rebuild the Eden we lost.

Regardless of your location or nationality you can probably see the seductiveness of this idea. It takes an unresolvable cosmic longing and advertises a resolution, projecting an endpoint to misery, waste, drudgery, toil. It sounds so much like the Gospel, which is why for most of my life I couldn’t differentiate between a faith in money and a faith in God.

In my twenties I joined an economic justice nonprofit with an office in the heart of downtown. The work was methodical and ambitious, involving collaborations with tech executives and philanthropists alike to complete projects that achieved, in the words of one of my colleagues, results in six months that took other nonprofits two years to even hope for.

Our methods were expensive, which meant you had to be comfortable chasing money to work there. For awhile I didn’t think this was a problem, especially because the hand of God and the invisible hand of the market seemed to operate in indistinguishable ways. Here I was, working in San Francisco in the middle of a tech boom, watching corporate donors turn on spigots of money in support of a good cause, and spending it in service of impressively worded goals and data-driven metrics that we always hit, every time. If God and Mammon were indeed separate entities, at least they seemed to share the same priorities.

If this period of my life had its own piece of religious iconography it would be the 19th-century painting by John Gast titled American Progress. The image features a line of settlers marching westward, beginning with men on foot and then on increasingly sophisticated means of transportation and colonization—men on wagons, then railways. Above them floats a woman in white who, although she symbolizes the American empire, evokes for me the cloud guiding the Israelites toward Canaan. The painting is like a mashup of all the billboards downtown with their messages around the transformative potential of money and power, all the chirpy slogans I repeated about economic opportunity for a better world, and all my vaguely syncretistic beliefs around God and American prosperity—an ambiently threatening picture of the human capacity for turning the wilderness into a paradise.

This kind of belief couldn’t last long. Bad theological ideas are usually exposed when they collide with circumstances they can’t account for, which is a mild way of summarizing what inevitably happened.

A year into this job one of my clients at the nonprofit was murdered. They had come from a Christian family to overcome a set of Dickensian obstacles; they had worked hard and were on the cusp of a major financial breakthrough. I couldn’t understand how someone I assumed to be unimpeachably prepared for success could be obliterated in a moment. They had been shot on a city sidewalk while attempting, of all things, to do a good deed.

After they died, most things at my job began to feel stupid. It wasn’t the job’s fault; the issue is that I had found this work compelling because I truly believed that godly intentions bankrolled by huge amounts of cash could change the world. Even if I was surrounded by intractable problems, like inequity that would not be solved in any of our lifetimes, I liked showing up at the office in my heels and crisp little outfits knowing that we had so many resources within our power to dispense. These spiritually charged acts of purpose and control were the best way I knew to refute every bad thing I saw in the world, but my client had done many things right and the outcome had still been unspeakable.

I didn’t last much longer in my role. I eventually found work with a nonprofit outside San Francisco and didn’t go downtown anymore unless I absolutely had to. Then after the pandemic, when everything began to slowly reopen, my husband expressed a desire to go visit SFMOMA.

The post-COVID landscape in downtown San Francisco matched my mood. All the familiar tech firms and finance buildings were still there, still gleaming, newly emptied. They looked like shrines to a religion no one cared about anymore. If all this was a metaphor it was kind of on-the-nose, but also not inaccurate. After I changed jobs things had continued to unravel; I switched to working with immigrant communities just as the Trump administration was sworn in and no longer felt that I understood anything about why terrible things happened to some families and not others, or why there was no direct correlation between goodness, wealth, and power. Some of the deserted buildings still carried their nonsensical slogans celebrating productivity and optimization, which made me feel both nostalgic and annoyed. The implied relationship between human effort and a better world no longer made any sense.

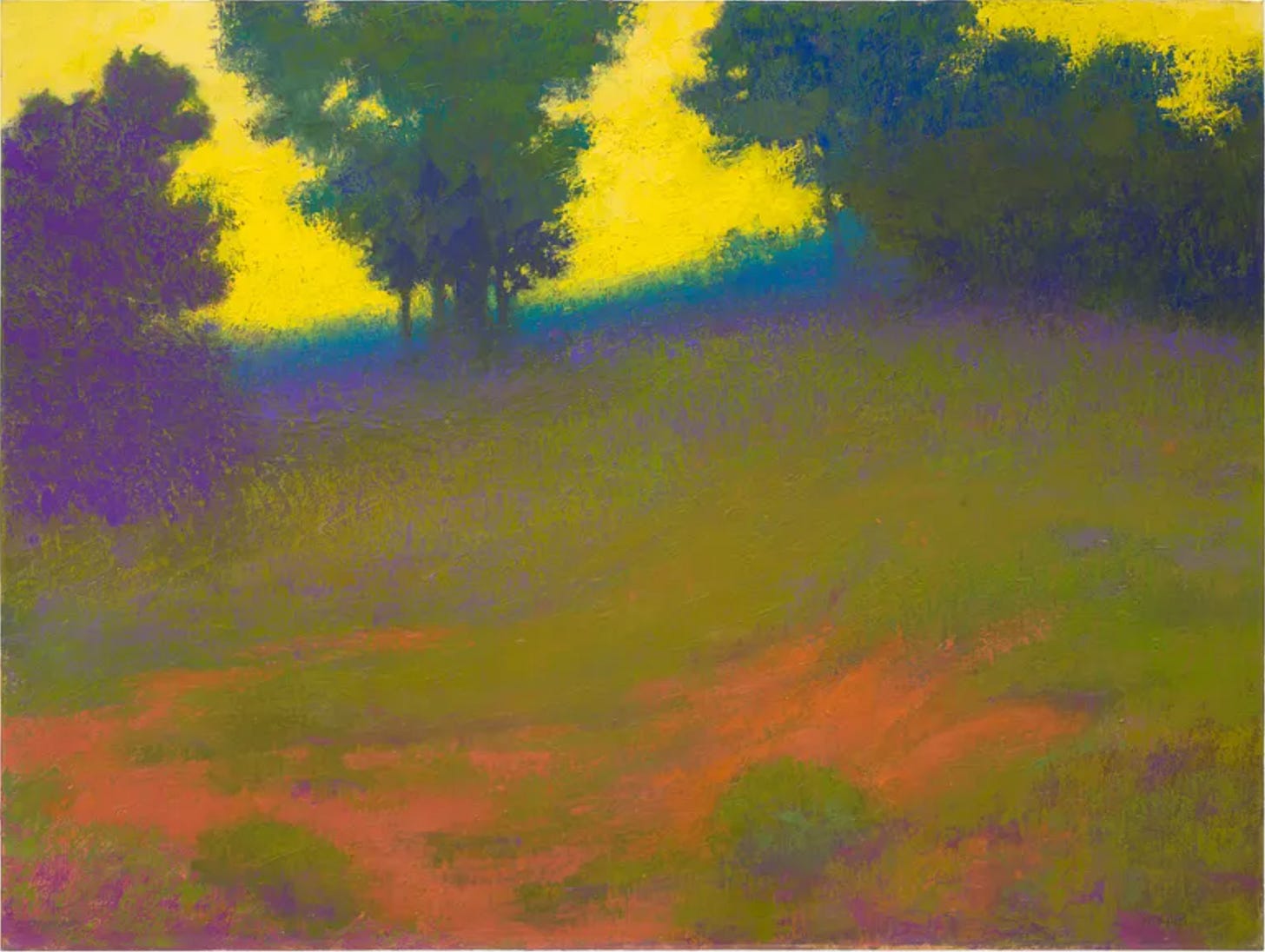

On the day we visited the MOMA there was an exhibition of works by the landscape painter Richard Mayhew. Mayhew, who is of Afro-Indigenous descent, says he paints the landscape with an eye to America’s most dispossessed, which means, among many things, that he doesn’t present the landscape to the viewer as if it is something to be dominated and possessed. The shift in perspective that comes from walking through San Francisco into a gallery of Mayhew’s paintings is so jarring that it is like being gripped by the shoulders and physically reoriented toward the world.

In Good Morning, Mayhew renders a dark line of trees against a neon yellow sky. The grass beneath fades into patches of bright red earth. As the viewer, you are positioned in this landscape at the angle of someone lying on their belly and gazing up at their surroundings. The experience of looking at this painting is the spiritual opposite of surveying the plains in John Gast’s work and thinking about all the ways we are preparing to remake the world in our own image.

It is not only the change in perspective that make Mayhew’s paintings feel incongruous to the city that houses them. His images seem realistic except for their unnatural, luminescent coloring. Good Morning looks like a landscape done on a bed of yellow highlighter. His other works are colored in a way to make the image appear unstable, as if the background is bleeding into the foreground. Seen through his eyes the world is both alien and familiar, capable of arresting you with its gorgeousness while erasing your sense of certainty about what you are looking at, or what it all means.

When things were going very badly at work and then very badly in the broader world, someone asked if this meant I was going to deconstruct my faith. I don’t remember how I responded but I remember hating the word almost immediately because it was so inadequate. The deconstruction of faith sounds like a self-directed process of sifting through your beliefs to determine what can be trusted as true or false. For those of us who suspect that our reasoning may have led us to form faulty conclusions about many important things, deconstruction sounds like the last thing we should be doing.

Anyhow, I couldn’t take credit for how much my faith in my own ideas had deteriorated. I didn’t feel like I was actively deconstructing anything as much as I felt like I was being interrogated by something outside myself.

The Old Testament was among the few things that comforted me during this time because I felt allergic to every form of sanctimony, religious and political, that seemed unable to acknowledge humanity’s inherent brutality and powerlessness against our own worst impulses. Within the Old Testament I was briefly obsessed with Job, which is why I think the Richard Mayhew paintings struck me the way they did.

Job endures a long list of traumas which I won’t pretend to identify with, but which lead him and everyone close to him to do what I felt myself to be doing: speculate uselessly about the nature of earthly suffering, suffering that apparently cannot be averted even by someone as rich and as good as Job. Their speculations are inconclusive. Towards the end of the book, the Lord arrives to speak for himself.

“Brace yourself like a man,” the Lord says, “I will question you, and you shall answer me.”

In response to questions that have never lost their resonance—why does the world seem so arbitrarily evil? Why does human goodness seem to avail so little?—the Lord speaks in a series of images. The earth, taking shape at the beginning of time. The ocean newly unleashed. Rain pouring across an uninhabited desert, stars being configured in the sky. These concluding chapters of Job are like a supercut of geological history in which humans barely appear.

There are no answers here, at least not the kind I’d like. The Book of Job left me with the image of God himself, standing in the center of time as planets form, life multiplies, as creatures live and die. The Richard Mayhew paintings made me feel dissatisfied and provoked in the same way. Evidently the anxieties that seemed so unique to me and my culture are old as time; the attempts to get a foothold on a shifting, unpredictable planet are no different.

I had come to the gallery with my whole body feeling like a clenched fist and yet when I saw those paintings I wanted to fall to my knees. Was this what God had wanted me to see? He was not answering me in words, only in shape and color suggestive of the terror, beauty, and wonder that come with being alive in the world, and with the sense that he remained at the center of forces that seemed so disastrously unmanageable.

I left the MOMA wondering if this was what it felt like for Job to stand before God with unanswerable questions, or for the Israelites to walk through the desert, led by a column of flame. Here was a presence wrapped not in certitude but in mystery, extending an invitation to enter in.

Yi Ning Chiu

Writer & Teacher

Yi Ning is a writer who has contributed features to Relevant and Teen Vogue. You can find more of her work here: yiningchiu.com

Thoughts on Yi Ning’s article? Leave a like and share in the comments!

Loved this. The last two years have included a journey through cancer, which I am likely to lose as it slowly spreads despite treatment. And Job has been my favorite book in Scripture. God engages Job not to just Himself but to do as you write. To invite us in. Not because we understand but because He does. Jesus said I AM the way. And how comforting that is.

Whenever I read Job, it’s always a total reframe for me. I remember God is master of the universe, and that there is a cosmic conflict happening that affects this world. I appreciate this article, and the description of how art can speak to our spirit.