Shouldn't Children's Books Still Be Beautiful?

Rebellion against some of the least humanity-friendly aspects of modernity

This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic features Nadya Williams

The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash; till he had dust in his throat and eyes, and splashes of whitewash all over his black fur, and an aching back and weary arms. Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing.

Yes, in case you are wondering, the above excerpt simply describes a mole cleaning up his home, and it's just plain beautiful writing. For a children’s book. About animals.

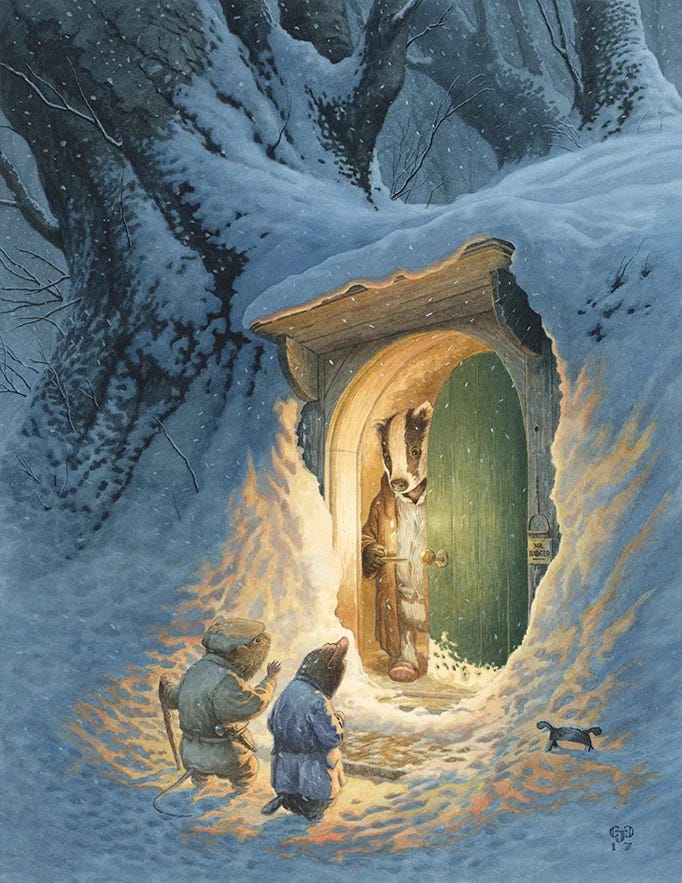

Indeed, you may have recognized the book in question: these are the opening sentences of Kenneth Grahame’s gorgeous Wind in the Willows, the most recent read-aloud book I got to enjoy with my kids. We usually have a couple of books that we are reading aloud together, about a chapter at a time. It takes us a couple of weeks or a bit longer even to finish each one, but this slow reading allows us to savor these books. And in this case, from the very beginning, savoring has been the mode.

We sometimes forget this, living in our pressure-cooker industrial-paced world, but we all, as human beings, have been created to crave and love beauty. It is, indeed, one of the features wired into us through the imago Dei. We love beauty because our Creator loves it and has created a world that is filled with it.

It is perhaps because of the beauty of the language that, as I have been reading this book, I found myself wondering: why do writers not write like this anymore? Indeed, it is a concern not only for children’s books but ones for adults also. I recently tried reading a very highly reviewed best-selling novel published in the past couple of years. I gave up after about fifty pages. Neither the subject matter nor the language seemed beautiful. Quite the opposite, rather. It was all, at the risk of sounding overly snobbish, utterly pedestrian, vulgar, unpleasant in all the mundane and uninspiring ways. Not even the general plot premise, quite interesting and creative though it was, could keep my attention at the end or convince me that this book would prove edifying in toto.

Perhaps not every book we read will fill us with a “spirit of divine discontent and longing,” but maybe more books in our lives should live up to this standard. For parents, such a goal is particularly significant: what we read with our children matters, because our time with them is so short, and how we spend it will form their tastes and character for life.

It may sound dramatic and, indeed, somewhat stress-inducing, but our children are only little for a brief window, a mere blink of an eye, we say in wonder as we reflect on the years that fly by. Should we not form them, therefore, from the very beginning to love beauty, wonder, and the transcendent? What if we placed this as a goal for educating them, especially in the early years?

Such a goal does require conscious thought about selecting books, and not for the reasons that those waging the anti-woke library wars propose. Rather, perhaps we should worry more about the dumbing down of language and content in too many books these days. Let me give you an example. A few years ago, I walked into a large chain bookstore, on a mission to find a Father’s Day present for my husband. I was thinking of getting a nice book that he could enjoy reading to our then one-year-old. When I described to a salesclerk what I was looking for, she proudly showed me the new release the store was actively pushing: Jimmy Fallon’s Dada.

I vaguely knew who Jimmy Fallon was. To be honest, the book’s contents did little to excite me to learn anything further about him—at the very least, it left me underwhelmed with his writing. Fiction book reviews often might include a disclaimer that there are (or are not) plot spoilers ahead. In this case, however, there is nothing to spoil, for there is no plot. There is, really, nothing of substance to this book. To be fair, someone might object that it is designed for infants. True, but does this mean a book ought to have no words, no beauty, no glimpse of glory at all? What does this say of our view of children’s intellect?

Do we not care to offer something greater for our children? Previous generations of writers and parents certainly did. From Alice in Wonderland to Winnie the Pooh to Peter Rabbit to We’re Going On a Bear Hunt to The Little Prince to the Narnia books, the best children’s books offer words that delight even the youngest listeners, rejoicing over the very sound of beauty spoken by a parent’s voice before they have a framework to know much else besides the security of presence and love. Then, as infancy gives way to toddlerhood and beyond, the beauty of the best books continues to delight through plot nd character, in addition to the sound of the words. Finally, as children grow older, the deeper message of such books offers more intellectual food to chew. Yes, Peter Rabbit’s misadventures or those of Toad in Wind in the Willows are certainly funny, but maybe I don’t want to do what he did, a child might think. Or he might realize at some point, perhaps when a bit older, that so much of life is just like every stage in the Bear Hunt: “We can’t go over it, we can’t go under it. Uh oh, we have to go through it.”

The idea of children’s literature is, in and of itself, a relatively recent phenomenon, I was reminded of this while reading aloud with my children George MacDonald’s delightfully strange (and oh-so-beautiful!) children’s book The Princess and the Goblin and its sequel, The Princess and Curdy. MacDonald, indeed, was a pioneer of such literature, historian Timothy Larsen notes. His work is deeply theological—as befits the Scottish theologian that he was—and has overt moral overtones. The good and the wicked reap their just rewards. Furthermore, both the good and the wicked are readily known by their fruit and even by the very touch of their hands.

The stories of great children’s books are memorable for all of these reasons—the beauty and depth of their plot, of language, of message. By contrast, what is the message of a book like Dada or many others like it that have been published more recently? It is like comparing the nourishing value of a fast-food meal to an organic gourmet feast. Sure, both are technically food, but the differences could not be clearer. Similarly, there is no lasting value in too many recent children’s books—and, for that matter, those intended for all other age groups. It is no wonder that so many children and adults of all ages today do not love reading. When the fare on offer is not worthy of love, it is a perfectly appropriate response not to love it.

So what are we to do? The answer is surprisingly simple. It has been in our presence all along—in our libraries and bookstores, even if not in the places of privilege reserved for the new and shiny books by pop stars and late-night show comedians. That answer is, of course, to select books for children that would edify their minds, spirits, and souls. This does not necessarily mean reading only old books, but it would likely involve reading more books that are older.

It may also involve reading more slowly—an approach that seems very pre-modern as well. Such reading is a rebellion against the fast-paced demands of programs like “1,000 Books Before Kindergarten,” which aims to promote literacy by encouraging parents and caregivers to keep a log to read 1,000 books before the child begins kindergarten.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with such programs, but they inadvertently promote the approach to children’s books as fast food rather than slow, beautiful reads. After all, if you are just trying to meet the quota of books, it discourages the reading of something lengthy like Wind in the Willows. It would, indeed, be much harder to plow through 1,000 books of this length and sophistication before a child’s fifth birthday. That, of course, is the point.

Chores and checklists can be helpful in allowing us to manage unpleasant but necessary tasks in life. Toilets must be cleaned, we know. And so, we gird our loins, put on rubber gloves, and handle it. But must we approach reading with our children the same way? I would encourage fellow parents to cultivate beauty in reading to children through the selection of books that call us to such a joy as this, rather than books that we read simply to fill in one more line in the list of a thousand. More than that, may we cultivate flourishing in the process by enjoying books that were not designed to be read fast but were written for our communal savoring and with an eye to eternal glory. Rebellion against some of the least humanity-friendly aspects of modernity can begin right here.

Nadya Williams

Writer & Editor

Nadya Williams is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023) and Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic: Ancient Christianity and the Recovery of Human Dignity (IVP Academic, 2024). She is the Book Review Editor for Current.

Thoughts on this essay? Leave a like and share in the comments!

Things we’re excited about at Ekstasis

Over the weekend, we hosted our first Inkwell event in London. It was an incredibly rich time to gather, eat, drink, and connect over poetry and literary contemplation.

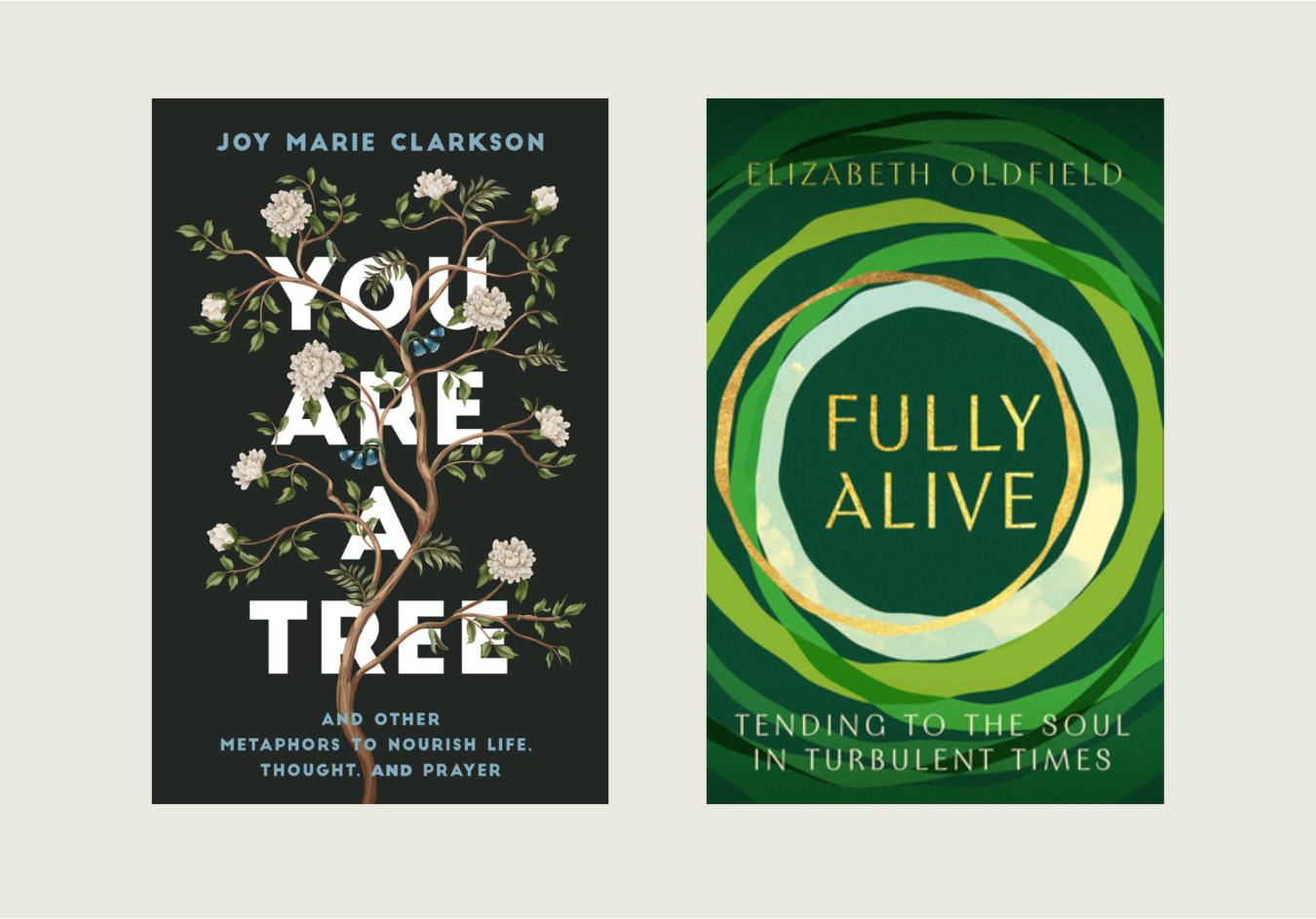

Two of the featured guests were Joy Clarkson (

) and Elizabeth Oldfield (), who have new books coming out soon that you can now preorder! Check them out: You Are a Tree and Fully AliveTreasures from the ether

The photography of Amy J. Lewis. Exhibitor at Inkwell and cover photographer featured on albums like Jonathan Ogden’s Songs From Home

Subscribe to Ecstatic, and order your Ekstasis Print Edition today.

As a septaguinarian who cut my teeth on the poetry of Walter de la Mare and Rudyard Kipling and the classics of children's literature, I agree wholeheartedly. It's where I began a passionate love affair with language and literature that fed my sense of idealism and my desire to be a writer. Schools no longer teach classic literature in their desire to be relevant, and children raised on the short attention spans of electronic media don't have the patience for "slow literature. "

I love the framing of choosing beautiful books as rebellion for the good of humanity. And the pushback against programs like 1,000 books before Kindergarten (whose purpose is undoubtedly well-meaning) allows me to exhale. Phew! We couldn’t do it, despite the fact that we read all the time in our house, and now I know why.

I was reflecting on some of these same ideas the other day while staring at DADA (a Christmas gift for our 10 month old from a family member) in our board book stack right next to a Sandra Boynton box set. All of my kids as babies have gravitated toward Boynton’s books. One of my favorites is But not the Hippopotamus, which opens “A hog and a frog cavort in a bog,” a pleasurable line for many reasons! To me, this proves that children—even babies—have the natural appetite for complex language and storylines; it’s up to us to give them access to the good stuff.