This Mid-Week Edition of Ecstatic features Mark Casper

YEARS AGO, I used to walk my old neighborhood in Charlotte, listening to podcasts as I paced beneath a towering canopy of willow oaks. At the time, one of my go-to’s was The Tim Ferriss Show, a popular podcast where host Tim Ferriss deconstructs world-class performers, extracting the tactics, tools, and routines normies like me can use. As I listened to episodes with titles like Tony Robbins on Morning Routines, Peak Performance, and Mastering Money or How to 10x Your Results, One Tiny Tweak at a Time, I hardly ever looked up to notice the trees.

Eventually, I did notice something rather odd in the show’s introduction. Over thunderous, electronic beats, I heard familiar clips from various films that together, embody the ethos of the show. “At this altitude, I can run flat out for a half a mile before my hands start shaking,” says Matt Damon as the trained assassin Jason Bourne, a nod to the show’s emphasis on peak physical performance. But the clip that stood out to me featured the voice of Arnold Schwarzenegger in the 1991 action classic Terminator 2: Judgment Day: “I'm a cybernetic organism. Living tissue over metal endoskeleton.”

In the film, the Terminator is a machine with human-like skin designed for one thing only: destroying its target. Undoubtedly, there is some tongue in cheek on Ferriss’s part to include a clip like this in his podcast introduction. But after listening to numerous episodes, I couldn’t help but get the sense that there was more truth in it than one would expect. A certain kind of ruthless efficiency—a “machine-like” approach to everything—seemed central to Ferriss’s vision of the Good Life.

WE ARE LIVING in the Age of the Machine, which Paul Kingsnorth defines as “the nexus of power, wealth, ideology, and technology” that has emerged to “replace nature with technology, and to rebuild the world in purely human shape, the better to fulfill the most ancient human dream: to become gods.”

We have not only embraced the way of the Machine, we have chosen to become machines ourselves. Consider how often we say we need to “recharge,” as if we were iPhones running low on battery. Or when we say we are “hardwired” for something. Our language is the canary in the coalmine: It seems we have concluded that to thrive in a Machine society, one must become a machine.

IN 2020, practical philosopher Andrew Taggert wrote an essay in First Things about the rise of what he called “secular monks.” According to Taggert, these educated, wealthy, urban men “embrace a secular ‘immanent frame,’ ascetic self-possession, and a stringent version of human agency.”

Above all, they commit to work—to working on themselves and on the world—as the key to salvation. Practitioners submit themselves to ever more rigorous, monitored forms of ascetic self-control: among them, cold showers, intermittent fasting, data-driven health optimization, and meditation boot camps.

Perhaps you have never gone full “monk mode,” eschewing hot showers for ice baths and grande lattes for shots of wheatgrass. (Lord knows I haven’t.) But it’s clear to me that their ethos has deeply embedded itself in our lives and cultural psyche. You do not have to be a young man plunging himself into a tub of ice daily to suffer from chronic self-improvement.

As Taggert outlines in his essay, the ideological river secular monks swim in is made up of several different streams: the pursuit of preparation (control), the pursuit of optionality (freedom), the pursuit of creativity (power), and above all, the pursuit of optimization (perfection). He summarizes their worldview:

“As human agents, we should divide our actions into means and ends, and if we’re good optimizers, we will discover and use the most effective means by which we can satisfy those ends. This defines human existence as [Tim] Ferriss sees it: an endless game of self-one-upsmanship.” While our methods may not be quite as extreme as these monks’ liturgies, I believe we have become just as obsessed with optimization.

Case in point: several years ago I started noticing an interesting trend. In conversation after conversation with friends and coworkers, I heard the same line: “I can’t remember the last time I read any fiction.”

This statement bewildered me to no end. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Eventually, it dawned on me: In a self-improvement culture, there is no room for art. There is only room for things which have an explicit, utilitarian purpose. Literature, art, poetry, films—these have no practical value in and of themselves. So why read a novel when you can learn ten principles from a self-help book?

IN THE INTRODUCTION to his book Culture Care: Reconnecting with Beauty for Our Common Life, artist Makoto Fujimura picks up on this very idea:

The assumption behind utilitarian pragmatism is that human endeavors are only deemed worthwhile if they are useful to the whole, whether that be a company, family or community. In such a world, those who are disabled, those who are oppressed, or those who are without voice are seen as ‘useless’ and disposable. We have a disposable culture that has made usefulness the sole measure of value. This metric declares that the arts are useless. No—the reverse is true. The arts are completely indispensable precisely because they are useless in the utilitarian sense.

When productivity becomes our highest ideal, we eliminate everything from our lives that isn’t deemed “useful” or “practical.” So we stop reading novels and poems (why bother?). Instead, we listen to nonfiction audiobooks (it’s more efficient that way) about “supercharging our productivity” while jogging, driving to work, or washing the dishes.

This never-ending project of self-optimization means we live on the precipice of burnout. We can’t even remember the last time we marveled at a sunset, stuck our nose in a flower, gazed in wonder at a painting, or laid our hands on the giant bole of a willow oak and lost ourselves in its sprawling canopy. We have not simply lost our humanity—we have opted to become mere “living tissue over metal endoskeleton.”

UNDERNEATH OUR CULTURE’S quasi-religious pursuit of optimization is the desire for perfection, which has its roots in a deep awareness of our brokenness. We are not the men and women we aspire to be. But the secular monk’s quest for perfection does not find Jesus of Nazareth nor his teaching of self-giving love for God and neighbor at its core. Nor do most of our efforts at personal growth. Unsurprisingly, self remains central to our project of self-improvement.

Like the secular monks, we desire to live without limits. To become impervious to decay, death, and the terrifying chaos of life. To “impact” the world through the indomitable force of our work. In short, we want to be superheroes. No wonder most tech innovations coming out of Silicon Valley market themselves as “superpowers.” It’s what we think we want most.

But there’s one small problem. “It’s increasingly clear,” writes Andy Crouch, “that superpowers come at a cost. Every exercise of superpowers involves a trade: You have to leave part of yourself behind.” In our relentless quest to optimize our lives and acquire as many “superpowers” as possible, we become less human. Less real.

IN ONE SENSE, a novel is indeed “useless.” There is no obvious practical value to it. The same is true for other art forms. You do not walk away from a Rembrandt painting, a Terrence Malick film, or a Mary Oliver poem with five practical action steps for how to get more done in less time.

Living in the Machine can sometimes feel small, tedious, and tawdry. Beauty cuts through our rationalistic, materialistic mindset and helps us reclaim the wonder we were made for. In his book An Experiment in Criticism, C.S. Lewis writes about the life-changing power of reading great fiction:

…the first reading of some literary work is often, to the literary, an experience so momentous that only experiences of love, religion, or bereavement can furnish a standard of comparison. Their whole consciousness is changed. They have become what they were not before.

Indeed, how can we be the same after sculling down the river with Ratty and Mole or trudging up Mt. Doom with Frodo and Sam? After scouring the seas with Captain Ahab or putting on a Christmas play with the March sisters? After wandering the Kentucky hillsides with Jayber Crow or burying our faces in Aslan’s mane alongside Lucy and Susan?

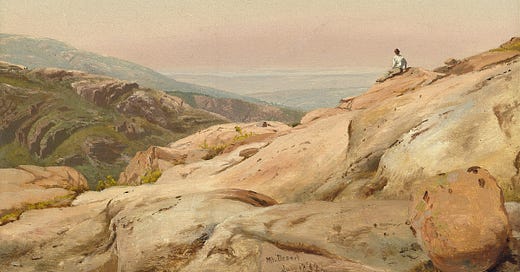

Great literature does something to us we can barely understand or even imagine. As Lewis says, it sparks an “enlargement of our being.” It opens up a landscape both within and without.

YOU WILL NOT FIND any of the works I just referenced in the self help section of a bookstore. And yet I consider them integral to the formation of my spiritual imagination. This is why art’s “uselessness” is the very thing that makes it indispensable: It teaches us how to be human again. Great stories remind us that we are more than just our outputs—grades, careers, successes, bank accounts, or possessions. They shake us awake from our rat-race way of living.

The Machine “wires” us to think and live in “-er” terms—i.e. better, faster, easier, more, etc. But the life we desire cannot be found by embracing the way of the Machine. We cannot “hack” our way to the Good Life nor optimize our way to flourishing. To the Machine, art simply “does not compute.” It doesn’t make logical sense. But great and “useless” art punches a hole in the industrial cage the Machine has built around our souls. And through this hole, the light of another world and way of being comes streaming in.

Mark Casper

Writer

Mark has been published in Mockingbird and Short Fiction Break. He writes towards the life we long for through the lens of literature, poetry, art, film, and theology on his Substack, The Kingswood.

What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

So true! I especially admit the fact that this machine mindset is creeping into us (me) silently and often unnoticedly. I have found myself even pondering the "usefulness" of spending time in deep fellowship with my Savior instead of doing something more "productive"—which is as ugly and shameful as it sounds—. But He Himself is beautiful. We were created for nothing less than pure, majestic beauty. All true beauty shines forth from Christ Himself, and it can lead us to Him. Let us behold Him through the arts until we are satisfied by His splendor.

Such a great entry here. These lines are incredible: "Great literature does something to us we can barely understand or even imagine. As Lewis says, it sparks an 'enlargement of our being.' It opens up a landscape both within and without." I was drawn to minor in English in college for this very reason—not because it made me more employable or useful to society or even more impressive to those who prize a well-read person, but because it felt like a way to both get outside of myself and have a mirror held up as well. Some of my favorite memories and learning experiences took place in my English classes as we discussed the fictional trials and tumult of characters who only existed on the page. What you share here is why I still feel it is so important to read great literature.