This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic features Sarah Clarkson

THE NIGHT BURNS BRIGHT and dark in my memory, a contrast of moods and scenes like a Caravaggio painting. The cathedral; bright, honeyed stone and gold instruments glinting on the altar. The kindness of my friend and his saving of an excellent seat for me as I skidded in, breathless, the sweet furor of bedtime rituals with my four children still an echo in my brain, a slight wildness in my eye. And the music, a many-layered brightness of harmony and word, hued like a crimson sunset to my synesthetic mind as a small choir sang a selection of ancient Orthodox chants and prayers.

I let myself breathe deeply as the music surged forward, let my eyes rove the warm, dappled space of the medieval church that summer night. But the longer I looked, the more darkness I saw. The shadows like dirty flocks of ravens in the high corners, the vivid stained glass windows I loved so well in the daytime obscured by night, the pain at the back of so many prayers I heard chanted, pleas for God to put an end to despair and death. And the darkness of my own weary heart when the concert had ended and I sat outdoors at a nearby pub and confessed to my long-time mentor and friend, a priest, that I found myself almost unable to pray.

A gentle, river-haunted quiet rose around us as my friend contemplated my dilemma. Laughter erupted from the next table. A horn blared from the road. My cider glass was cold in my hand and I held its chill against my face as the discomfort of my confession ebbed away.

I WAS DISTURBED by my incapacity to pray, by a sense of growing inward lethargy, and the attendant grey silence that seemed to meet it from the heavens. My faith, after a diagnosis of mental illness in my teens, was something I’d fought hard to keep. The story of my belief was one of fierce and hard-won exultation, of beauty triumphing over depression and deep fear. I studied theology for four years. I’d written full books in witness to the gracious help I had found in God. But the past years had ushered me into a different season of interior life, presenting me with the challenge of sheer exhaustion. I was unable to perform my faith by prayer or long hours of study and devotion, and in that lack, I felt abruptly uncertain of myself, and of God.

I’ve always been a little haunted by the allusions in Scripture to those who “fall away.” What does it mean to lose sight of the thing you most love, the lodestar to your universe? Falling away… it sounds like just losing your grip in an offhand way, one afternoon when things got a bit busy and life was too stressful. Or maybe it was something that could happen when life asked more than you could give, if say, you lost several people you loved, or bore two babies amidst lockdowns and loneliness, or moved three times, or battled appendicitis and pneumonia and just endured a darn hard spate of years.

Like, say, me. Maybe in the weary end of that you really could just… drift away from prayer, and then from faith, to find yourself lost in a dark ocean, miles from the surety and passion that once anchored your story.

MY DISCOMFORT WAS HEIGHTENED by having watched a number of my friends deconstruct their faith and find themselves unable to put the pieces back together. I understood the deep pain that began their unravelling, the betrayal of others and the confusion that seemed to further shatter their belief into unmendable pieces. But even in the worst days of my illness and doubt, I had somehow never lost my sense of God as potently good and real… until, maybe now? Until this spiritual inertia. I found myself returned in thought to the early days of my faith when I feared an indifferent God. My interior exhaustion left me with the startling fear that a great, uncaring silence would descend when my own voice died and my prayers failed.

I glanced up at my friend when the panic of that thought burned my face. I found him already looking at me, all compassion. He leaned forward and spoke. His suggestions were simple.

“If you can’t pray, just say one prayer: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. And find an icon to pray it with, every day,” he said.

So, very weary, a little desperate, and a little more than skeptical, I did. I didn’t know what else to do.

THE ICON I CHOSE was the Eleusa, or the Madonna of Tenderness, an ancient image of Mary cradling Jesus. Their cheeks touch as they lean into each other, mother and child holding hands, a circle of undisturbed affection created by the curve of their bodies and Mary’s capacious arms. But though everything speaks of their almost exclusive intimacy, their gaze is turned outward to the viewer in something I felt at first as challenge, but with each passing day more keenly, as invitation.

I set the icon up in a corner of the paned window by my reading chair. Each morning, I snatched ten minutes to sit down and silently pray. Nothing else. And looked at the icon. I knew the basic theology behind iconography, the idea of the image as a kind of window into the landscape of the divine. So I tried to let the icon look at me as much as I looked at it. There was a strange kind of daring in this exercise for me.

For much of my spiritual life, I had come to my times of devotion tensed for effort: to read, to concentrate, to think rigorously and pray fixedly. I felt I must think the right thoughts and conjure the correct feelings in order to reach God. Now, I did almost nothing. I waited on him to attend to me, feeling a little audacious. It was the strangest thing, sitting there with no exertion but that of gazing at the little Christ, asking for mercy, waiting for I had no idea what. For something to shimmer at the back of the icon and answer me?

THE STRANGE AND STARTLING thing—was that it did. Not, of course, immediately, and not in an actual shimmer, but in a potent sense of a great affection hovering all around me. It was like watching a storm gather on the horizon, only this was a gathering of mercy in my interior skies. I felt my gaze increasingly drawn into the circle of love imaged in the cradling of Mary and her Christ, and knew myself tenderly drawn to share their joy.

It was not something I understood. A reader and writer my whole life, a questioner of doctrines, with two theology degrees under my belt, I found it all a bit ridiculous. Words nor explanation could encompass it. My rational mind groped to untangle this mercy, but my soul simply stood by in welcome. I found myself in the presence of mystery.

AROUND THE SAME TIME, I began to read Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. My first try, twenty years before, had been badly timed. Back then, I’d been raw and grieved by the new diagnosis of my mental illness. I craved very certain answers about God’s will, his mercy, and his might. Dillard’s pilgrim-hearted writing felt like a threat then—too formed by the problems of suffering, too willing to deal in unanswered questions. But now, as my effort eased, my hands opened, and the answers I thought I knew were pushed aside by something benevolent and great, I rediscovered her writing and found it heady and wild. “Our lives are a faint tracing on the surface of mystery” she wrote. These words now sang in concurrence with my growing sense of this benevolent presence who came in response, not to my strength, but my frailty.

I realized one day that the primary shape to my devotion had become that of need. Which brought me to the instant and astonished understanding that much of my faith life had been built on the assumption that the way I prayed or the Scripture I studied could conjure God’s help and presence in my life. I found myself suddenly unsure of what God demands. I used to think he asked so much; holiness of life and a swift performance of righteous deeds and a clear conscience and constant prayer. But in the turbulence of my past difficult years or the season of prayerless angst that followed, I had offered almost no fixity.

My own deconstruction began to gradually take place, but not one of disintegration. What came undone and fell away was not the substance of my faith, but the performance I thought it required and the means by which I thought God could be summoned, predicted, and even in some sense controlled by my language, my discipline, my managed emotion. I was led by my need, not to an abandonment of faith but to its unexpected enlargement. Not a decay, but a ripening. I read a poem by Denise Levertov one day in which she opens by railing at God for the suffering of the world and then, like a child whose strength has been spent in sobs, ends in brief assertions.

I do nothing, I give You

nothing. Yet You hold me

minute by minute

from falling.

I knew exactly how she felt.

IN THE AUTUMN, a few months after the concert, I sat one evening in a different sanctuary, the tiny “lady chapel” of the parish church pastored by my Anglican priest husband. Every few weeks he gets one of the retired priests in the congregation to lead the Wednesday service of Eucharist so he can stay with the children and I can attend. I stumbled in at the last minute, knelt, and joined in the liturgy. As usual, I felt keenly that I brought little to the table. But as the thought came that night, after months of sitting in the presence of love, asking for mercy, I was halted by a sudden insight. I bring nothing to this Table and never have, for it is the Lord’s and he is the giver. And the gift he gives is himself.

How do you get mystery in your hand, how can you taste Love in a broken world? You hold it open before Christ’s table.

I LOVE THE IRISH way of speaking about a person, “Why look, it’s himself.” It reminds me a little of how God describes himself in the Bible as “I am.” That night, as I took the bread of God’s table into my hands, a cheeky voice inside of me said, “Ah look, it’s himself.” Because it was. And this is the mystery. Not that I have taken heaven by the trappings and attainments of my gritted faith or incantational prayers but that Love has put himself in my hand. There he is. A slight heft of tangible mercy, bread for my stomach and health for my soul.

And prayer rose in me like laughter, a mirth of gratitude spilling over into effortless praise.

Love ever ancient, ever new. I never lost it, I needed only to lose the idea that I could summon something already given. I have come to believe that Love is the mystery that arrives within our stories, vast and benevolent, thrusting himself into our hands, our broken hearts, our weary, prayerless minds. My faith will always shift and change, not because he is less true but because his kindness is so much greater than my frail imagining. Love grows. Fear crumbles away. Faith ripens.

And joy gathers, a great brightness upon the horizon of my heart.

Sarah Clarkson

Author & Writer

Sarah Clarkson writer whose work centers on beauty and grief, story and quiet. She studied theology at Wycliffe Hall in Oxford with a focus on theodicy. Her most recent book is Reclaiming Quiet, written to answer my own questions about what it means to have a quiet mind in a fallen, screen-driven world. What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

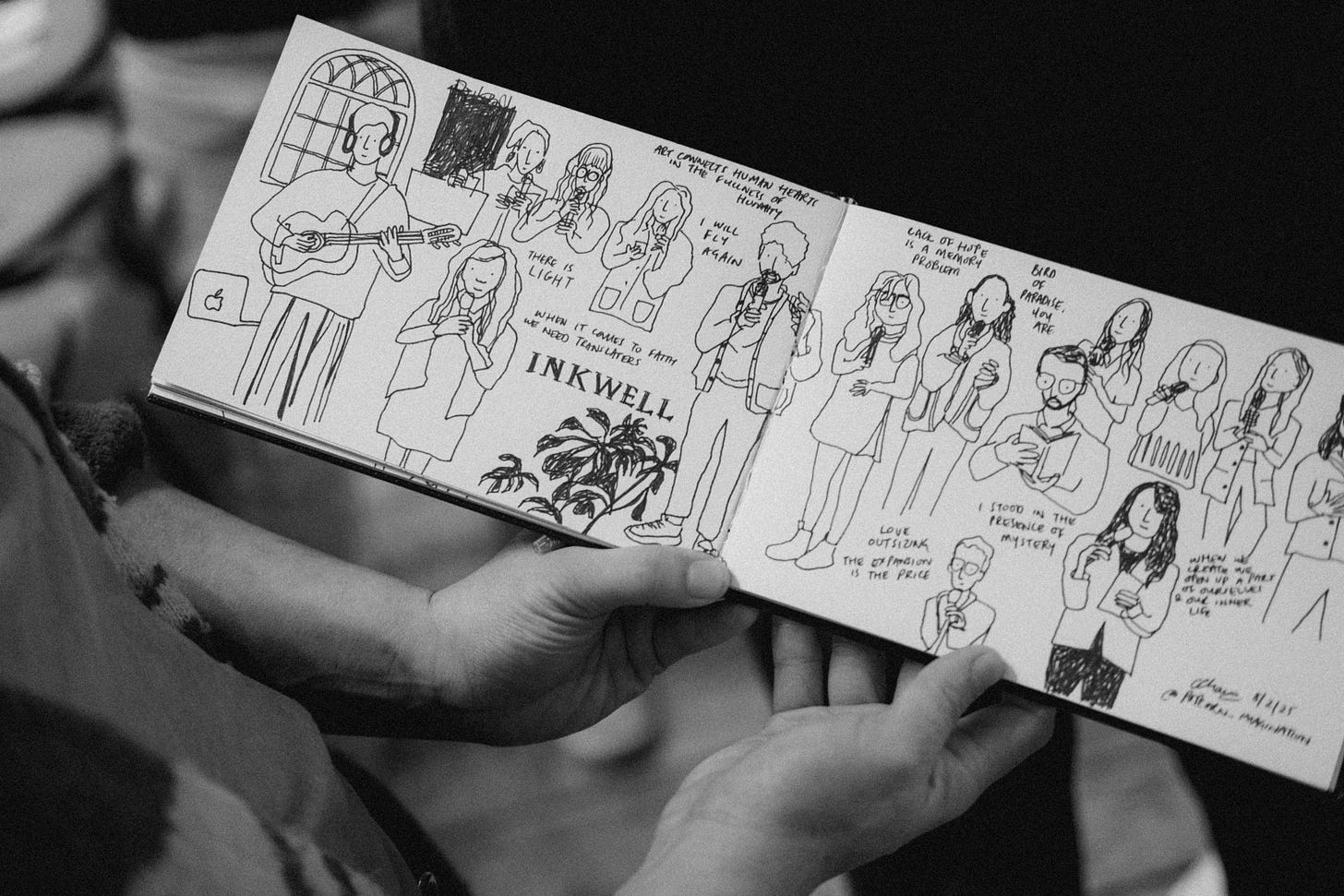

Today’s essay was recently read live at our London Inkwell Evening. Our next Inkwell Evening is in Nashville, TN on March 21. Let’s gather for an evening of art, storytelling & friendship to find transcendence together.

"Ah, look, it's Himself." I don't think I'll ever be able to approach the Lord's table again without thinking of this!

Thank you. What I see in your comments is the beauty found not in strengthening or building one's faith, but in discovering the source of faith right there with you all along. Faith knows how to grow; you made a great garden.