The True Work is More Practical than Performative

Interview with Justin Giboney on what we can learn from the Black church's public witness

This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic is by Yi Ning Chiu. This month’s features are brought to you in partnership with Fuller Seminary.

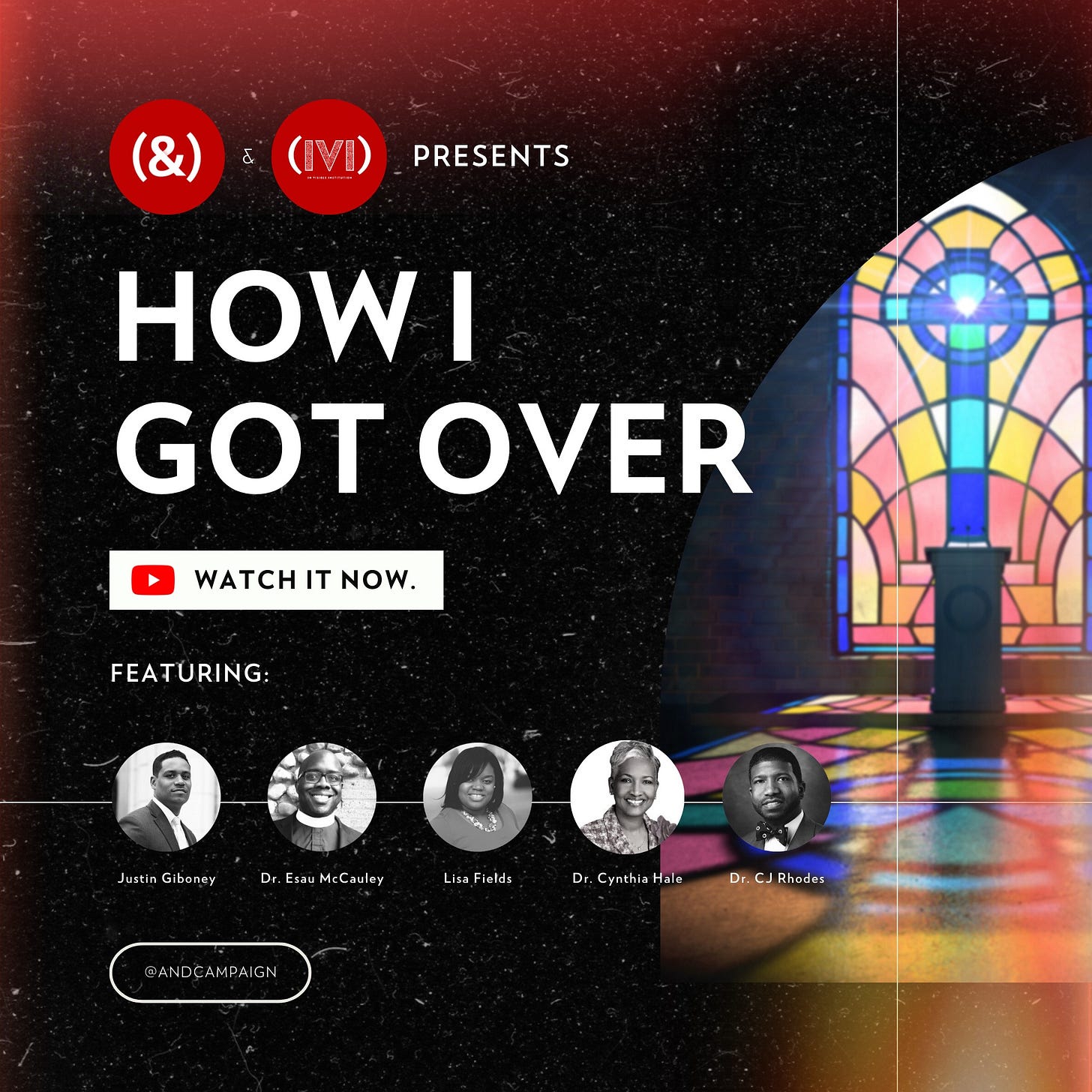

The AND Campaign’s documentary series, How I Got Over, traces the Black church’s history of devout faith and robust public witness. Ecstatic spoke with Justin Giboney, president of the AND Campaign and co-author of Compassion (&) Conviction, about why this history is crucial to navigating the present. This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Yi Ning Chiu: Your new documentary series sounds like it’s simultaneously narrating the Black church’s history and addressing a contemporary state of mind. It repeatedly emphasizes the need to understand how the Black church’s commitments to social justice and equitable political representation are rooted in its Biblical convictions. Why is that understanding so important for you to communicate in this series?

Justin Giboney: If you look throughout the history of the Black church, from its founding as an invisible institution during slavery to all the events that came afterward, Biblical faith is what held everything together. What we wanted to do was let people know about the rich history of the Black church—what came out of the Black church, the role that it played in the community as a whole—and how every cause we advanced had the authority of Scripture as its basis. To move away from that truth is to move away from the essence of the Black church.

YC: There are multiple places in our culture where I think people want to cite the Black church as their influence in order to validate their cause, but they often do so without giving serious consideration to the church’s orthodoxies.

You’re from Georgia, so you probably saw an example of this with the Warnock versus Walker runoff during the most recent Senate race. People on the far left hailed Warnock as the spiritual descendent of Martin Luther King Jr., and held him up as a representative of the Black church. People on the far right said Walker had more traditional beliefs, and was therefore a truer representation of Black Christians. These kinds of conversations exacerbated an already divisive political climate. How do you think our public discourse would change if everyone had a stronger grasp of the Black church’s history?

JG: For one, we would realize that the Black church is not a monolith. And I think it would also give us a path forward out of these kinds of culture wars. One thing I think people did with Warnock and Walker was push them to opposing sides of a cultural debate. And when that happens, I think we lose the essence of what the Black church is.

What the culture war currently does is separate social justice from moral order. Broadly speaking, there are these two sides: one cares about justice, and one cares about morality. These divisions have not historically existed within the Black church, so to see Walker and Warnock get pushed into these two categories meant we couldn’t see a nuanced picture of who the Black church is.

Again, we are not a monolith. But if you listen to people like Dr. Esau McCaulley, he would tell you that the primary stream of the Black church is going to be orthodox, and is going to value the authority of Scripture. What I think the Black church currently has to offer this country is to show that justice and righteousness aren’t mutually exclusive—that to fight for social justice while at the same time having a high view of Scripture and Christology is possible. These things are not in conflict.

We have a strong example of that in the history of the Black church which, I think, is valuable at a time when everyone is so polarized. In a divided culture, many Christians on opposing ends of the political spectrum will use part of the Bible, but neither side is putting together a full, multidimensional biblical ethic in a way that I think has been done in the past.

YC: So what do you think happens to the public discourse when we get sloppy about understanding the history of the Black church and how we invoke it?

JG: I think we just take a piece of it that's useful and leave the rest. So if this happens on the right, people will take pieces of church history that seem to emphasize color blindness, but take it out of context—for example, citing Martin Luther King Jr. on focusing not on the color of our skin but the content of our character, then ignoring the rest of his legacy.

On the left, people will take the church’s social action, but leave the commitment to the authority of Scripture and its absolute truth. So what you are left with is parts of church history and scripture that get commercialized for what people want to use it for.

YC: I think we already see this within our broader political discourse. I’m curious to know what you think happens to Christians specifically when we don’t know our history. What comes to mind for me is this: following George Floyd’s murder, a fairly broad spectrum of Western churches, regardless of their specific denomination or racial makeup, became activated in their pursuit of racial justice. That lasted for maybe a year. After that year, the initial enthusiasm really seems to have simmered down. How do you think a more robust understanding of Black church history could help the church continue onward in its engagement with justice work?

JG: That's good. This goes back to your other questions, I think, especially for folks who lean a little more conservative. To truly understand the Black church's history is to understand that the Black church was orthodox. This isn’t necessarily the same as saying it was conservative, but to say it was orthodox is to help people understand that its pursuit of justice was not a superficial “social gospel” movement. It was something much deeper and much better connected to the Scriptures than that.

Our social action wasn’t performative when compared with what you see today. Part of the problem, and why you saw things fizzle out after the George Floyd protests, was that our culture became so performative. Activism became a social media thing—people taking the perfect picture at the perfect time. It seemed so glamorous, when the true work was never glamorous. The true work is more practical than performative.

The Black church’s historic activism has really been about the sense that we know something is going to change because God told us he’s a liberator. Even when we don’t see it, we believe it. So we’re doing it to glorify God, not because we’ll get some likes online or because certain groups like when we use politically charged language.

I think the Black church’s history helps us get back to the practical side of our witness, rather than being preoccupied with who says what in our culture, and being about the language and performance of it all.

YC: Okay, I have some follow-up questions about this. For one, that whole idea that social justice is just a watered down version of the Gospel is a critique I’ve heard in different church circles. In those settings, the moment someone says we should work towards racial equity, they will be accused of departing from the true Gospel. Where do you think that behavior comes from?

JG: It comes from experiences of majority culture Christians. Within their historical framework, you have a separation between orthodox Christians and liberal Christians within the white church that occurred in the last century. Those lines are based more on dividing the evangelical from the mainline church: folks who were going to focus on purity and morality and folks who were going to focus on the social gospel.

When majority culture Christians address Black people, they put us within that same framework and say, “Okay, if you’re addressing social issues, you must have chosen the social gospel side.”

But what the history of the Black church will tell you is that we weren’t part of that separation at all. That wasn't a framework for Black Christians. So we didn't see that false dichotomy that came out of that theological battle within white Christianity. Our context was different, but people have judged us by another context because they don’t know our history.

YC: That is so interesting. It’s like there’s an intellectual colonization that happens within the church, where majority culture Christians have articulated standards for evaluating a minority community’s faith, even if that community wasn’t included in the initial conversation.

JG: Even if you weren't part of that argument! That’s the same thing that goes on with progressivism and conservatism today—we're going to put our framework on you and even if your decisions weren't made based on that framework, or that same context, we're going to put you in one of those categories, because our framework is the only framework.

YC: How much do you see that attitude paralleled in mainstream conversations about ideology and belief outside the church? I’m thinking about the broader conversations in which people try to slot different communities along the spectrum of “progressive” versus “conservative.” How much do you think those mainstream categories actually influence what happens on the ground within your local church context, and the Christian thinkers you interact with?

JG: I mean, I think it has a lot of influence. For instance, if you went into churches during 2016, you had people literally almost fighting in the church over the election. When you watched cable news, you got those two sides that would be arguing, featuring people who are super progressive or super conservative. So a lot of Christians, even Black Christians, now can’t articulate politics or culture outside of this progressive and conservative framework. That’s the framework they’re starting to use.

What we're trying to do with this documentary is say that's not the only framework. It’s better not to create that false dichotomy. I challenge some of my peers by saying you’ve got to be able to articulate what you’re saying outside that framework.

YC: When you talk about the conservative versus progressive dichotomy, that makes me think about the fact that there are gatekeepers to all our information sources. There was an Asian American lawyer who wrote an essay last year in which she critiques the kinds of Asian writers that get platformed, and how closely they need to hew to a publisher’s sensibility around race and identity. Do you see that happen for Black voices? And if you do, where do you think people need to be looking to get a more varied diet of Black thinkers and theologians?

JG: Absolutely, that happens in the Black community. If you’re on progressive platforms they’re going to choose people who say things that fit their narrative. That’s just the way it is. Same thing for conservative platforms. They’re used to inviting people who say what they want somebody Black to say.

If you look for people like Dr. Esau McCaulley, pastor Charlie Dates, Lisa Fields, Dr. CJ Rhodes—these are people who defy that dichotomy. If you’re going to ask them a question, depending on what the question is, you may see them as conservative or progressive, or something that doesn’t match either of those labels.

These thinkers are tied to the tradition of the Black church, and so they innovate from that foundation. They’re seeing the world differently and being deliberate about not falling into the trap of left versus right.

YC: Let’s loop back to something we were talking about earlier. We discussed how some people view the prioritization of racial justice as a departure from the Gospel. On the flip side, I see so many people leave the church because they think it’s not radical enough for their politics. What do you think a documentary like How I Got Over can show folks who feel their commitments to justice and equity are incompatible with their faith?

JG: It shows you that there is an orthodox way to do justice. From an American historical standpoint, I don't know that there's anybody who's done social action better than orthodox Christians. If you look at the largest social movements we’ve had, like abolition and the end of slavery, or the Civil Rights movement, they were mostly run by orthodox Christians who accomplished all these things while truly believing in the Bible.

People don’t know what orthodox Christianity is. People think it is whatever white evangelicalism says it is, but I would argue that sometimes the majority culture church was not necessarily orthodox, and where they made their biggest mistakes wasn’t in moments where they stayed too close to the Bible, but when they wandered away from the Bible, following their own self-interest. When majority culture churches did things like saying they were Christian and then acting bigoted, like when Christians fought against the Civil Rights movement, they may have had the right doctrine and did not apply it correctly.

Let me show you some examples of some truly orthodox Christians: Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass—these are people who did it the right way. Don’t let a distortion of orthodoxy woo you away from the authority of Scripture.

YC: That’s good. What do you think is the most important thing for the larger body of Christ to understand about the Black church right now?

JG: That it has a rich history, that the primary stream of that history is orthodox. That there's something we could learn from it today in this culture war, and that it's actually healthy for majority culture Christians to step out of their context and look to another context for answers.

Yi Ning Chiu

Writer & Teacher

Yi Ning is a writer who has contributed features to Relevant and Teen Vogue. You can find more of her work here: yiningchiu.com

Thoughts on Yi Ning’s interview? Leave a like and share in the comments!

In the midst of our polarized society, it can be tempting to resort to either indifference or resentment. We all recognize a need to transform our present reality, but often struggle to imagine how. Fuller’s DMin Public Theology Cohort seeks to address the pressing questions of our culture through the formation of a new theological paradigm centered on beauty.

The divine beauty of the gospel serves as the primary inspiration and catalyst for unifying a divided church and reigniting its mission in the world. Cohort participants will develop a robust integration of theology, culture, and the arts that will sustain and guide all aspects of their ministry.