Today’s feature was originally published in Ekstasis’ summer collection.

This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic is by Arthur Aghajanian

In one way or another, any serious discussion about our fascination with images draws us back to the work of Walter Benjamin. In his influential essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935) Benjamin explained how original works of art possess an aura; a presence in time and space that mass-produced imagery lacks. In a time when art and culture are increasingly digitized, Benjamin’s ideas about aura raise important questions about the relationship between technology and human experience.

I’ve found over time that my orientation to Benjamin is helpful in thinking through a variety of specific issues related to digital society and its emphasis on speed and reproducibility. Benjamin even helps with questions around the meaning of the family snapshot, which has been complicated in a society where family and social relations are commodified through reality television and social media.

On a recent afternoon, I found myself musing on the popularity of digital sharing and the way we publicize images of family, when I remembered a group of photos of my own that were taken during my first years of life. I anxiously exhumed the album containing this treasure from a packed hallway closet. Then, as I leafed through miniature prints documenting my infancy, I discovered an ironic reversal of Benjamin’s idea: That under certain conditions, modes of mechanical reproduction may also possess an aura.

Many have reacted to the rise of digital technology and the attendant dematerialization of culture by seeking out physical objects, particularly handmade ones with authentic qualities (Benjamin wrote that aura emanated from authenticity). Nostalgia often accompanies such efforts, as seen in the mass harkening back to retro technology like flip phones, vinyl records, and even typewriters. More than merely promoting nostalgia, certain images, existing as objects produced through outmoded technology, can function in their authentic capacity (and resulting aura) as invitations to spiritual contemplation; an avenue that promises a return to the real.

A printed photograph is an object that carries an image in its skin. For those who print their own images, the concreteness of the photograph is easy to appreciate. My first serious efforts with photography were in art school. Making prints from film negatives was physically and materially more intensive than projects I undertook for any of my courses in drawing, painting, or graphic design. The black and white photos my classmates and I developed in the campus darkroom were the products of an arduous, exacting material and chemical process. Bringing an image to life was a rich sensory experience. Spooling film onto metal reels in the darkroom, I’d feel the film’s texture against my fingers—thin and smooth but also slightly slippery from the emulsion. Softly clicking as I’d wind it into place, I’d feel its tension as I guided it onto the spool. In the close quarters of the darkroom, the acrid aroma of fixer mingled with the sweet tang of developer. As we would scrutinize contact prints, experiment with exposure times, and bathe paper, nothing was predictable. Submerging the light-sensitive paper into a pool of developer, I’d hold my breath and wait. Like a ghostly apparition, a slice of the world would slowly appear.

To one degree or another every photograph from my childhood and family history is a personalized sacred object; a spiritual memento. Benjamin argued that the images produced in modern culture, increasingly widespread through the advent of the printing press, lithography, photography, and film, led to distraction. That contemplation, which requires attention, isn’t possible when we’re overloaded, provoked, and incited by images from every direction. Now consider the staggering acceleration of image production since Benjamin’s time! Yet when I retreat into silence with these old, mechanically produced images, I am drawn deeply into their world.

It matters that the personal connection and emotional resonance that makes old family pictures meaningful is experienced through an obsolete form of photographic printing, one that cannot be replicated. Delicately holding these prints between my fingers, I wonder at the miracle of their survival despite the decades. Having been shot on film and developed on paper, these images are fundamentally different in nature from the images we take of ourselves and our families today. In the era prior to the widespread use of digital cameras that began when I was a young adult, flipping through the cardboard pages of a family photo album approached the singular experience of art that Benjamin was referring to in his essay. It was to contemplate a unique object and to be transported beyond yourself.

In part, family photographs are heirlooms, recording a history of relationships as they change hands and travel across generations, families, and places. The fragile materiality of photographs from my childhood emphasizes the transience of what’s pictured: the people and things I’ve held dear. But as objects with a history I can feel—fingers tracing contours softened and frayed with time, they also invite contemplation. In this way, I equate them to liturgical objects.

Although frozen in emulsion, these images can mediate presence the way icons do. Each time we dig out an old album, flip through its half-remembered treasures and nurture our intimacy with what we find there, we’re enacting a ritual that evokes reverence, wonder, and even gratitude. Just as a sacrament is an outward sign of an inward grace, the images that touch us most deeply speak to the sacredness of life. When I commune with family pictures, I’m not simply being nostalgic. I am acknowledging a love greater than myself, one that sustains all of us.

In my ruminations on the theological implications of the family photo, I found myself revisiting a work I had been introduced to in my later art school days as a graduate student. Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, first published in French in 1980, remains one of the most important books of criticism on photography, and high on the reading list for students of visual culture. A deeply personal work, it explores the emotional resonance of photography in ways that touch upon the medium’s sacred qualities. Though Barthes resists delving into the spiritual implications of his ideas in much depth, his use of religious language throughout the book—which is essentially an extended meditation on the nature of the photograph—provides a helpful guide for those of us who seek to recognize God’s hand working in the midst of our cultural production.

Barthes' writing becomes more personal in the second half of the book as he reflects upon an old print of his mother as a child, what he calls the Winter Garden Photograph. This image captured what for Barthes was the essence, or “eidos” of photography: what he referred to as the Real and the True. In the secular reception (literary and cultural criticism, philosophy) of Camera Lucida, Barthes’ use of these terms could be frustratingly vague. Looked at from a religious perspective however, things come together rather clearly.

In Camera Lucida Barthes distinguishes between two elements in a photograph: studium and punctum. The studium hearkens to Barthes’ semiological work. It is the system of signs in a photograph that carry historical, cultural, or social meanings. Those elements in the photograph which can be named and understood. The punctum is that which will “...break (or punctuate) the studium.” It is a detail in the photograph that unexpectedly pierces the spectator’s inner being: “A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” The snapshots of my childhood speak emphatically in both ways.

Image and material are fused to create sacred objects that have miraculously survived over decades as small, fragile pieces of paper, presenting fleeting realities of life. Each aspect of these objects is an embodiment of our transience, like feathers on the wind. I’m reminded of the teacher’s words in Ecclesiastes. He compares life to vapor (the Hebrew word is hevel), but many versions of the Bible translate hevel as the word “meaningless.” Of course, life isn’t meaningless. Like vapor it’s transitory, and the evanescence of the photograph mirrors this truth.

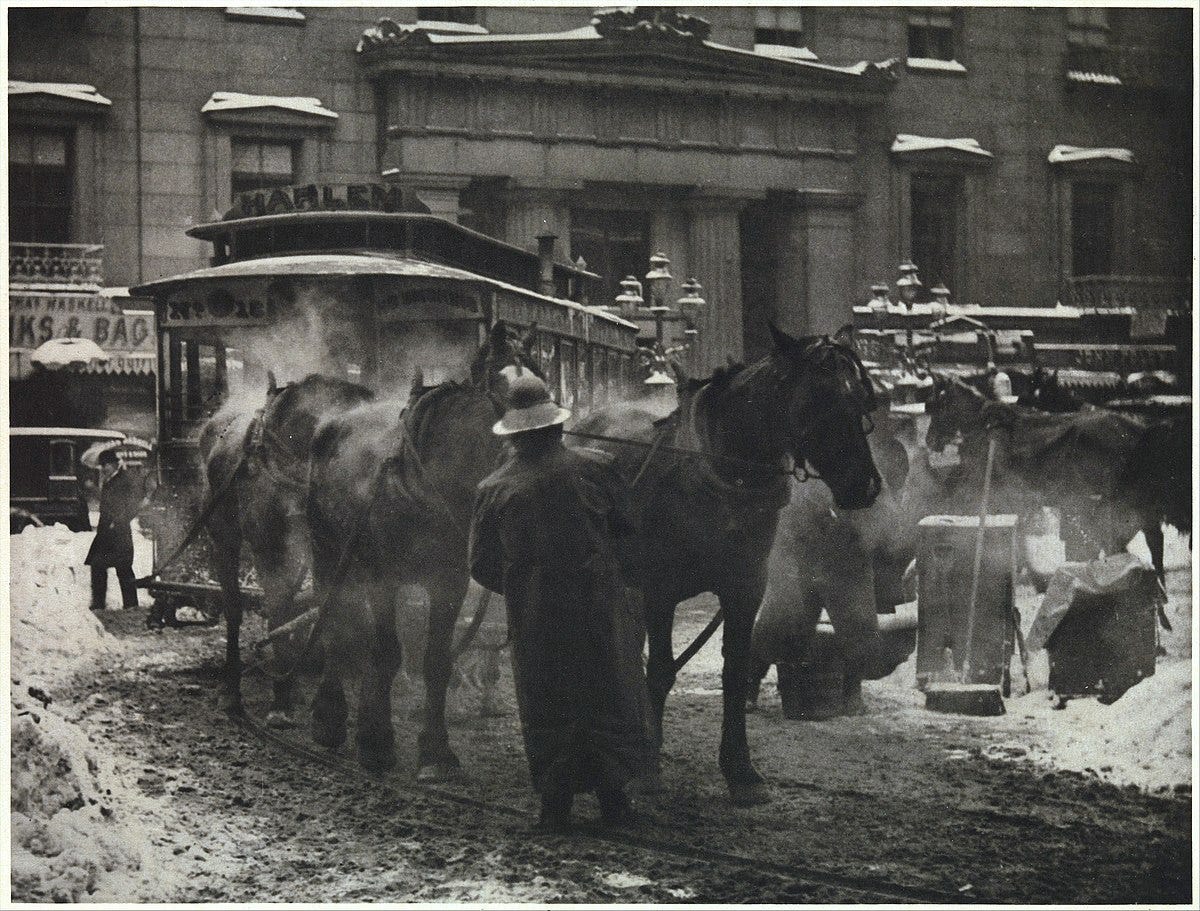

Barthes characterizes the Real, as well as the Truth of photography, as ungraspable. As he writes of how a photo mediates presence, he muses on the themes of time and death. Both of these are underlying themes in the book of Ecclesiastes. Photographic images appear like apparitions, congealing on photo-sensitive paper, an ephemeral object, bound to decay and disappear with time. Among the images Barthes includes in Camera Lucida is Alfred Stieglitz’s famous photograph, The Terminal, New York. In it, steam rises off horses as a horsecar driver waters them down on a freezing-cold day. The horses seem to dissipate like hevel. All is vanity because nothing of this world is permanent.

As the family snapshot transmits the presence of an absence, it awakens love, thereby absorbing us into the continuum of the Real. This Real is what Paul Tillich called “the Ground of Being,” a metaphor for God. Love is the shared reality of God. Interestingly, Barthes describes the punctum’s effect on the viewer in terms of grace. He writes of it as a gift of sudden awareness, an enlightenment, and how the photograph resurrects the people and places of our past. As grace is the outpouring of God’s love, when we’re open to it we may indeed be “pierced” with sudden awareness. From a contemplative perspective, brought about by quiet reflection on humble objects, the invisible movement of grace becomes visible.

Arthur Aghajanian

Writer & Educator

Arthur is a Christian contemplative, essayist, and educator. His work explores visual culture through a spiritual lens. His essays have appeared in a variety of publications, including Radix, Saint Austin Review, The Curator, and many others. He holds an MFA from Otis College of Art and Design. Visit him at imageandfaith.com

Beautifully written! I absolutely loved this and hope to read more like it.

I *love* the notion of a photograph becoming a liturgical object. Thank you for your insights and poignant writing!