This Weekend Edition of Ecstatic features Paul J. Pastor

Charity itself is full of war.

— Charles Péguy

I. A brief family anecdote of war.

MY GRANDFATHER PAUL, whom his grandchildren and great-grandchildren would one day affectionately call Gum, was the youngest of three children, born in 1925 in Canton, Ohio, to Pásztor Janos and Pásztorne Sitka Gizella, new immigrants from Hungary.

Paul was 16 years old when America entered the Second World War in 1941. When he was 18, he was drafted into the war in Europe and assigned as a private to a specialized rifle squad, mounted on “half-tracks,” as a point man for General Patton’s armor. His older brother John was 25—an officer, he went in on Omaha Beach, at the very center of the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

From the Normandy beachhead, John’s unit moved deeper into France before encountering a particularly well-planned German ambush in a particularly cursed rural hedgerow. Caught in the fire of heavy machine guns, small arms, a tank, and mortars, John left the momentary safety of the ditch, pulled a bazooka off a dead man, incapacitated the Panzer blocking their exit route with a well-placed shot, and was promptly shot and torn by shrapnel from the explosion of a nearby shell. Being a Pastor, he survived.

For his bravery in that single action, Uncle Johnny was awarded a promotion, two Purple Hearts, and the French Legion of Honor. He went home, where his barrel-chested body had a long recovery. For the remainder of his life, flecks of German steel would work their way out of his back while he slept. In the sunny light of early morning, his wife, Cozette, would pick them off the sheets and plink them into their trash can in Burbank, California. He had seen, if my memory is correct, only about 20 days of combat.

My grandfather Paul was assigned to General Patton’s Sixth Armored Division (the “Super Sixth”). He would serve in all of Patton’s five major campaigns, including the Battle of the Bulge. His were the first Allied boots into village after village held and hotly defended by the Germans. Casualties to his unit were enormous. He was hardened for many months by extreme conditions of stress, against an organized and determined enemy with a defender’s considerable advantage. He refused multiple promotions, having had time to notice the relative rate at which officers tended to die. He fought a very different war than that of his brother. It was long. It was exhausting. It made him quiet.

He could not then have known, as the European summer reddened to autumn and went corpse-blue with winter, that he would survive. Many decades later, he would tell me, one of the four men in our family named after him, that he had fully expected to die, and that all the rest of his life that followed he considered to be “extra,” a sheer gift.

He could not have known then, his thumbnail bruised blue by the bolt of his Garand, that he would marry his high school sweetheart, Irene, who would become my feisty, dark-eyed grandmother. Nor that he would graduate from college, earn a master’s degree, and complete his PhD. He could not have known the respected teaching career, nor the children, nor the grandchildren, nor the great-grandchildren, who would all, always, speak of him with reverence and affection, like one speaks of a chieftain or a wise man.

II. An unsettling aside.

I WILL VENTURE that I know something about you. Perhaps things are going very well for you, or perhaps they are going very poorly, but in either case, I expect that you may be “losing heart.” What a cliché that phrase can be in the wrong mouth! But I mean it in the deepest sense of the term—you are becoming discouraged. The cœur (French for “heart”) of your courage draining away.

Perhaps, in spite of your belief, in spite of your best efforts, there is a sense of meaninglessness washing at your roots like the waves lap at a tree beside a swamp. It comes from everywhere and from nowhere, it seems. There is a wrongness in the world, difficult to name, and it is growing.

Only you know where the contours of this discouragement fall in your own life, but are they not there? It is in the fabric of our times. It drifts down to us with the changing of the years. You think it is politics, but politics are only the skin of the thing. So it is with culture, watching people on every side of you make fools of themselves because of fear, or ignorance, or one of the fashionable follies of our day. You would even chalk it to “human nature,” but it feels neither natural nor human. Perhaps, remembering some old preacher, you might blame it on a “fallen world,” but it does not feel that it is quite in the world at all. Whatever it is, you feel it nosing itself against your heart.

III. The culture of Pretend.

CONTEMPORARY LIFE in the developed world is characterized nearly everywhere by the quality of Pretend. Our politics, business practices, relationships, social media feeds, and more are all defined by pretense—having the appearance of depth, competence, quality, or beauty, but the actuality of shallowness, incompetence, cheapness, and the tawdry or ugly. Pretending (which is not Imagination) has infected nearly every aspect of our lives.

This is not uniquely an American phenomenon, but America has perfected it through the irresponsibly used power of stories. I am not only referring to the stories that we think are stories (novels, blockbuster films), but also to things we do not automatically recognize as such. Consider advertising, for example—which uses the tools of story (plot, character, setting) to influence you in favor of a product, perhaps, or away from the other party’s political candidate. Or consider the carefully curated algorithms which tunnel through all of your digital life, working sleeplessly to understand your tracks in order to craft the story of you—your demographic, your interests, the likely trajectory of your short- and long-term life—in the hope of delivering just the right thing at just the right time to get you to ______ (buy, vote, share). Your life narrative is being used to shape the future of that narrative, becoming a trajectory aimed at money. Like the devil on your shoulder in old Looney Tunes cartoons, something is always whispering in your ear.

This culture of Pretend exists because contemporary life has become exceptionally insulated from reality. Never before in human history has such a small percentage of people had to deal with the beautiful and horrid essentials of human life—directly touching birth, illness, death, food production, war, peacemaking. There are now mercenaries to serve in every human struggle (usually on the other side of a screen), from buying our groceries to burying our dead. When the Real intrudes (and it always must intrude), there are experts to help control it or minimize its inconveniences to the majority of the population.

Polite society goes to great lengths to pretend away its enemies. Conflict, like other inconveniences, is outsourced for someone else to handle: the police, the lawyers, the military, a drone operator sitting in an air-conditioned office park while killing people in a foreign war zone. Enmity, as most of us experience it, is often either performative or superficial.

But what do we lose when we lose our enemies? In fact, to be a person without enemies would be a pitiable state. Would it not mean that one stood for nothing, or that one was nothing? Pasta may be free from enemies, I suppose. Who could hate a lump of warm, damp noodles? You might prefer something else, but hatred is the wrong category. A person, however peaceable, cannot be free of enemies, not without being of about the same spiritual depth as pasta. Jesus, after all, did not tell us either to ignore our enemies or to destroy them. He said to love them.

And how can you love your enemies if you have none?

IV. Of the holy enmity between the Children of Life and the Children of Wrong.

THE CENTRAL STORY of the entirety of the Christian Scriptures is of enmity. This conflict is between the offspring of Eve and the offspring of the Snake. The symbolism is clear here—Eve’s name is directly related to the Hebrew word for “life” and breathing; the name of the Snake (נָחָשׁ, or nāḥāš) carries a sense of being crooked, wrong, or twisted. Serpentine. This enmity, symbolically, is between Life and the Children of Life, and the Children of Wrong.

By Wrong, I do not mean an arbitrary moral wrong. At least not at first. I mean a Wrong that is infinitely more basic and more horrible than what we commonly think of as sin. The Snake’s twistedness was not about breaking a rule. It was about erasing Rule. It was not a temptation to disobey God. It was about trying to pretend into existence a world without Obedience or without a Real God at all.

This is the Wrong of our true and only original Enemy. It is a Wrong that would, if it could, un-nature every bit of nature and un-good every speck of the “very good.” It is a Wrong so total and sad and infantile and absolutely pointless that it would rejoice to make the bedrock soft, and all the water hard as flint, to make fire cold, and cause the wind to clot and fall to the ground in useless gobs. It is a Wrong that would make light dark, just for the hell of it, and which would turn every book to gibberish, and defecate on every sacred image. It is a Wrong that would make the fathers and mothers abandon their children and embitter children against their parents, that would make male nothing and female nothing, and turn every child into a self-important, lascivious adult and make the adults babble and tantrum like brats. A Wrong that would empty every pleasure of all joy and every life of all love.

This is the cosmic war that forms the black-and-scarlet backdrop to every human life. It is the one holy enmity. It is good to have the Wrong as enemy, to hate it with all your being. This is what love looks like when it meets what would undo it. This is why, in the Psalms, we ought to rejoice when we are told that the Messiah will break the raging nations with the Creator’s rod of iron, and why we ought to cheer with St. Paul when he tells us that Christ, through his resurrection, has led all the fallen Powers in triumphant procession, like a conqueror. It is why we should be out of our seats and shouting when the “great dragon” seen by St. John—who tried to swallow the Woman Clothed with the Sun—is cast down forever into the sea and the great pit. We are at war, and every soul you have ever met is a piece in that great game, becoming, one day at a time, either more a Child of Life or more a Child of Wrong. It is an honor to have such enemies. It is an honor to be such an enemy. It means that we are who we have been told we are.

At this point, you may be thinking I am going to make this political. You may think I am now ready to tell you which category of person you now have permission to hate, and who I would like you to vote against, or despise, or fight. But I will not do any of that. You may hate no one except Hatred itself. You may kill no one but Killing. Our weapons are not of this world, and our trust is not in princes nor their chariots.

IV. Danger! Danger!

THERE ARE FOUR typical human responses to danger. Freeze, flight, fawn, or fight. To freeze is to lock up. You do nothing. You just stand there. Bang. This is the deer in the headlights. This is the response of those who, unprepared for the confusion and adrenaline and surreality of true danger, just stop. It is the worst possible response.

Slightly better, from the perspective of basic survival, is flight. This, of course, is getting yourself the hell out of there. This is not usually a permanent fix, but it buys you some time, I guess.

Fawning is the most pathetic option. One tries to ingratiate oneself with the danger. One flatters the bully or licks the hand that holds the billy club. One offers the bully little treats, and laughs at all the bully’s jokes, and tells the bully how glad you are that he’s your friend as he’s shaking out your wallet and cussing you.

Then, of course, there is the option to fight. Here is what is glorified in all the big American stories. This fighting does not always mean resorting to outright violence, but, of course, violence is always on the table. Once begun, this will never end. Like flight, fighting may buy you some time. Perhaps it will buy you a few generations of time, and sometimes this must reluctantly be done. But it will never be permanent. It will always halfway serve the Wrong even as it pushes it back. It will always cost part of you. Even the best soldiers will carry within them some “spot in France.”

With a little thought, I am sure that you can think of examples of Christian responses to culture that would fall under each of these categories—perhaps even people or public figures who might typify each one. So which of the four will it be?

Well, there is a fifth option. To feast.

Part 2 coming later this week…

Paul J. Pastor

Author & Editor

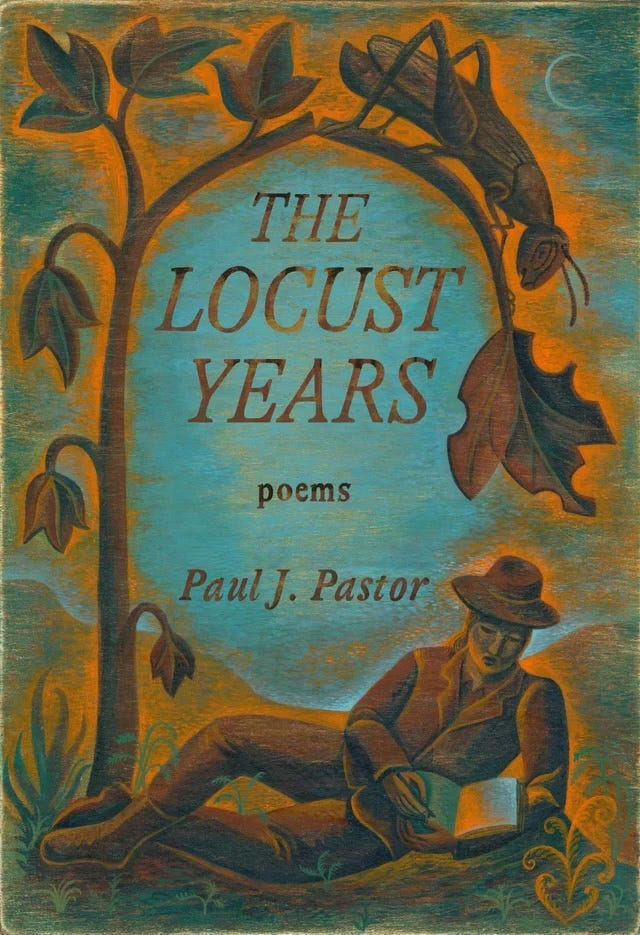

Paul is a Contributing Editor for Ekstasis & Executive Editor for Nelson Books, an essayist, critic, author of the forthcoming book The Locust Years and Other Poems. What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

Get your copy of Paul’s new work, The Locust Years!

Profound. I thought of 10 people I'd like to send this too. Fantastic in its simplicity....Beautiful truths. Oh more and more of this must go out into the world.

This is fascinating-looking forward to part 2. Well chosen words and excellent writing!