This Mid-Week Edition of Inkwell features Peter Battle Biles

I DON’T KNOW how many times I’ve walked around the local park after work over the last few months. I typically go home, change, feel the vague need for activity and exercise, and drive the mile to the peaceful lake surrounded by post oaks, pines, and spoiled geese, sidewalks stocked with sleek runners, bumbling old men with headphones, and restless teens ribbing each other at the docks.

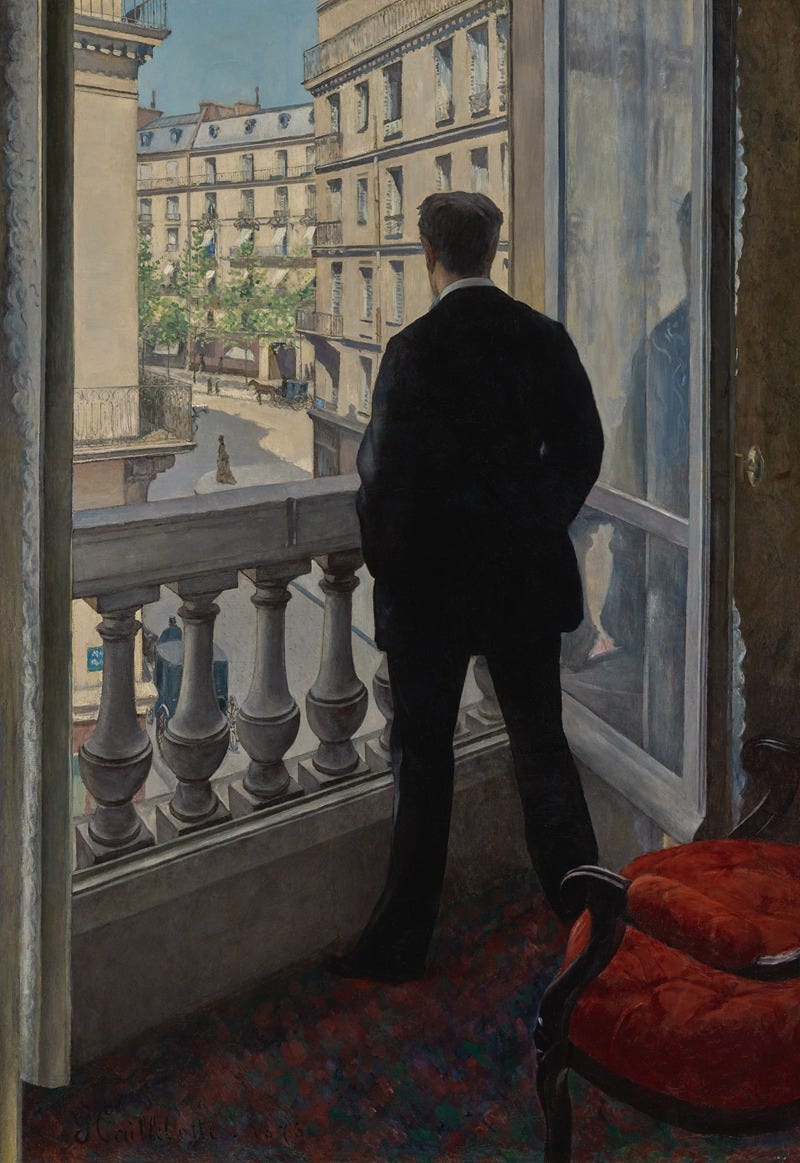

Some people are walking together, chatting happily, or with knitted brows, but I typically take the jaunt alone. Not always, but often. It’s a nice way to cap off the afternoon. Recently, it’s dawned on me that my circular pilgrimages around the park loop might just be a picture of post-college life in the 21st century: Walking close to other people but hardly ever talking to them, ducking under the boughs of beauty but hardly ever stopping to truly look. The question is—will I even try?

THIS ISN’T A NEW feeling for me or for countless others. In the summer of 2019, I wrote an essay called "Loneliness at College," a testimony about my time at Wheaton, a small university just outside of Chicago, where I struggled to find meaningful community. Was my initial isolation the fault of the school itself? No. Wheaton, however, advertised its rich Christian community as a selling point. Yet, after a year of dreary freshman dislocation, I didn't feel any closer to finding it. It was only over time that relationships began to form, deepen, and help heal my sense of alienation. In order to have friends, I learned that I actually had to be a friend.

I’m learning that lesson again, five years later.

A CAMPUS MINISTER once told me that one of the most challenging parts of college ministry was warning students that community does not come easily after college. At Wheaton, teachers begged us not to conflate student body chapel sessions with church attendance. When community and even church-like experiences have been cultivated for you, the post-college life can suddenly feel like a barren wasteland.

You may be able to guess what happened after my time at college. After graduation, the rumors of a far-off disease suddenly turned into a worldwide shutdown. College was over, its friendships uprooted, and the brave new world was now mediated through Zoom sessions on my laptop. Overnight, I went from interacting with my friends every single day to going weeks without one wholesome conversation.

As the years after college began to tick by, some of those college friendships started to fade. Whatever obstacles there are to community, I realized that connecting deeply with other people must entail commitment—it takes effort and you have to sign up for the long haul. It involved a level of effort that I wondered if I was even willing to give.

Whatever friendships we may have forged in childhood or during chemistry lab at the university, they are often overshadowed by the urge to self-actualize through career, travel, and pleasurable experiences—drives which remain dominant in American life. Even Wheaton, for all of its strengths, occasionally fell prey to a kind of careerism as personal fulfillment narrative. Everyone talked about faith and vocation in terms of getting significant careers and positions that would advance the kingdom of God, but it was only through the gentle prodding of my philosophy professor that I was reminded of the original purpose of the liberal arts: to be formed into a particular kind of person—one who is free to love his neighbor as himself, to commit to other people.

“What if instead of showcasing all the philosophy majors who became lawyers and think tank researchers, we highlighted the philosophy major who went back home to become a husband and a father?” he once told me. I still think about that.

AFTER GRADUATION, many of us landed back where we started four years prior. COVID-19 was dislocating for everybody, of course, but starting my post-graduate life in a context where human gatherings of more than ten people were suddenly not allowed didn’t exactly blunt the blow of isolation. While many good things happened during the following years, including the launch of my writing career, meeting a few key friends and colleagues, and gaining experience in my field, I struggled to ever find and commit to a local church body. I didn’t get married. I don’t have any children. And sadly, I don’t see the friends I made along the way. They live in Boston, Denver, Washington DC, New York City, Seattle, Tennessee, and Singapore.

I started to wonder what the point of any of it was. I had moved around so often, never staying in one place long enough to put down roots. I watched friends marry, have children. I scrolled X reading think pieces about technology addiction and loneliness. I wrote think pieces about technology addiction and loneliness. But eventually, I had to try, in my distractible and frenetic state of mind, to ask myself if I was at all practicing what I preached. The answer was a forthright no. In fact, I was doing the very things I kept warning against: depending on a virtual world for a vague semblance of community, and treating the real people in front of me as somehow less vital than the online avatars out in the ether.

Community, I realized, is just uncomfortable. Calling old friends to have a catch-up conversation is uncomfortable. While I’m always glad I made the call, it remains hard, for some reason, to make that initial step. My theory is that we have created a world that subtly destroys our relational compasses. It gives us just enough of a sense that we are connected to the world while at the same time removing us from the actual things we need to be fully human.

So, strangely, I had to ask myself a difficult question: Do I even want community, or do I just say that I do?

IN The Great Divorce, Hell is a metro of solipsistic ghosts. The residents of the dreary, grey town that Lewis illustrates can’t stand having any neighbors. They have to keep moving to the outskirts, building farther away from the center. If they want friends at all, they have to cater precisely to their specific wants and needs. Sound familiar?

The internet has become a remarkably complicated mirror of the self. There is a morsel for everyone in its labyrinth of distractions. It hoards personal data and spits out streams of personalized algorithms in response. Of course, this isn’t to say that digital technology is wholesale bad. There is obviously a way to use the phone, laptop, and iPad as tools for creation and a genuine means of connection (hence, the phone calls to my friends scattered across the country).

All I’m trying to say is that technological comforts and virtual replications of community can seduce us into believing we no longer need “the real thing.” It lulls us into slumber, dulls the pain, and over time, might convince us that we don’t actually have true, spiritual needs for communion with God and other human souls. I find myself perilously close to the rich man Jesus warned us about in Luke 12, who stored his grain in his barn and declared that he was all set for a merry, pleasurable life. “I’m good!” the contemporary version of the character might say. “Got my phone, got my porn, got my Instagram friends, got my DoorDash. We’re chillin’!”

Combined with the message that self-actualization, not self-giving relationship, is the goal of life, it is no wonder we find ourselves lonely, unmoored, and living more or less meaningless lives.

THE LONELINESS EPIDEMIC is real. The meaning crisis is real, too. I’m just one small figure in a massive and tidal trend. People are struggling. In terms of gender dynamics, fewer men are attending college than women—they are checking out. A vast number of 18- to 25-year-old men have never approached a female to ask her out on a date. In addition, men and women are veering into separate political camps. With politics now as the national religion, how can we expect the sexes to cooperate, let alone get married and have children, if they can’t stand who the other person voted for?

I don’t begin to pretend to have all the solutions to the isolated fragmentation of society. The main thing I’ve learned, though, is that if I want community, I can’t wait for it to come knocking at my door holding a pizza with a Bible study ready. I have to step outside, reject the technological web of comforts I’ve invited into my midst, and commit to a particular people and a particular place.

Dallas Willard said grace is opposed to earning. It’s not, however, opposed to effort. Sometimes I wonder what would happen if more of us simply tried. What if I tried joining a community group at my new church? What if I tried to sign up for that service project? What if I gave that guy a ride home? What if I invited three or four friends over to play a card game and drink tea? Maybe it is mustard-seed faith, but apparently, that’s what God likes to work with. It is hard. It is uncomfortable. But the alternative is being, as author Sherry Turkle puts it, “alone together.” The alternative is waiting for the world to cater to my felt needs, and the internet is more than happy to oblige. However, it will ultimately rob me of the meaning and connection I claim to want—and do genuinely need to flourish.

The college campus can lead to lifelong friendships. I am continually grateful for the friends I made there, despite how hard it has become to keep up with them all. But the local church remains the essential community that we are called to cultivate. Any good church community will doubtlessly include people we would otherwise never be friends with—the types of people internet algorithms and college mixers would never send our way.

Maybe, though, that’s the point?

Peter Battle Biles

Writer & Poet

Peter Biles is the author of four books, most recently the short story collection Last November. His writing has been featured in Plough, The Gospel Coalition, Dappled Things, and several others. He writes a Substack called Battle the Bard.

What did you think of this essay? Share your thoughts with a comment!

Every time we move, I feel how challenging it is to get the social machine moving again. Inertia is powerful, but it can make life easy and mindless. Finding your people in a new city takes intention. I frequently feel pesky. Perhaps being a bit of a nuisance is what it takes to insert ourselves into the already established rhythms of others? It is easier in transient cities, where other newbies are also looking for people with whom to spend the holidays. In order to make friends, you have to reach out far more than is comfortable. I probably wouldn't do it for myself, but with children in tow, I grit my teeth and swap numbers with other parents like someone is paying me to bulk up my contacts. With practice though, we can normalize almost anything.

Thank you Peter. At the age of 85 I reflect on many things. I have a foto of my wife and me standing out side of the KiIns, the home of c s lewis. It always reminds me of his custom of taking a hour at the start of every day to write letters to many, including children. It spurs me to communicate.. blessings, chuck keortge